OBO, Central African Republic — The hunt is officially over.

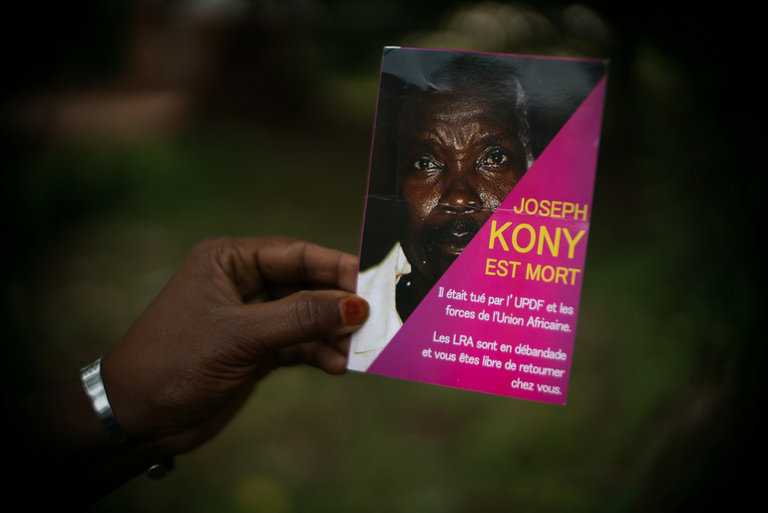

“Joseph Kony is dead,” announced American-made leaflets dropped from a helicopter in the

“>Central African Republic in recent weeks. “The war is finished.”

The claims that Mr. Kony, the notorious leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army, has died are false, though. American officials say such disinformation is often intended to sow confusion and encourage defections from Mr. Kony’s group, which has committed atrocities in the region for decades.

But while Mr. Kony has evaded capture, the United States and the Ugandan military decided to end their search for him in late April, abandoning the international effort to bring him to justice.

Now, after eight years of being deployed in the Central African Republic, the Ugandans are leaving behind their own trail of abuse allegations — including rape, sexual slavery and the exploitation of young girls.

Dozens of accusations of sexual abuse have been documented by the United Nations, human rights groups and survivors themselves. It is a “widespread problem,” said Emmanuel Daba, a local victims’ advocate investigating sexual violence by the Ugandan military.

OBO, Central African Republic — The hunt is officially over.

“Joseph Kony is dead,” announced American-made leaflets dropped from a helicopter in the Central African Republic in recent weeks. “The war is finished.”

The claims that Mr. Kony, the notorious leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army, has died are false, though. American officials say such disinformation is often intended to sow confusion and encourage defections from Mr. Kony’s group, which has committed atrocities in the region for decades.

But while Mr. Kony has evaded capture, the United States and the Ugandan military decided to end their search for him in late April, abandoning the international effort to bring him to justice.

Now, after eight years of being deployed in the Central African Republic, the Ugandans are leaving behind their own trail of abuse allegations — including rape, sexual slavery and the exploitation of young girls.

Dozens of accusations of sexual abuse have been documented by the United Nations, human rights groups and survivors themselves. It is a “widespread problem,” said Emmanuel Daba, a local victims’ advocate investigating sexual violence by the Ugandan military.

According to internal United Nations records, peacekeepers in the Central African Republic have documented allegations of the rape, sexual abuse or sexual harassment of more than 30 women and girls by Ugandan soldiers. Beyond that, they found 44 instances of girls and women being impregnated by Ugandan forces.

“Several women and girls reported they had been taken from their villages by U.P.D.F. members and forced to become prostitutes or sex slaves, or to marry Ugandan soldiers,” the head of the United Nations peacekeeping mission wrote in a letter to Ugandan authorities last June, using the initials of the Ugandan People’s Defense Force, the Ugandan military.

“I was working out in the fields when it happened,” one girl who said she’d been sexually assaulted by a Ugandan soldier told The New York Times in an interview. “The man came behind me without me noticing. He grabbed me. Then he raped me in the field.”

She was 13 years old at the time, she said, and she became pregnant. Her parents went to the nearby Ugandan military base to report the crime, she said. Ugandan officers said that the soldier had already left the country but that they would “bring him to justice and put him in prison,” said the girl.

She is now 15 and says no action was ever taken.

Jeanine Animbou said she was 13 when a Ugandan soldier used to send a motorcycle taxi to her mud hut and take her to his military camp. The sentry let her in without any problems, she said.

Ms. Animbou, who is now 18, said she met the Ugandan soldier while walking down a dirt road here in Obo, a town used as a base in the search for Mr. Kony. The soldier said he wanted to start a relationship with her, promising to take care of her and give her things like soap and food, she said.

Living on her own in a country where most people make less than a dollar a day, she said she agreed, seeing few other options.

The Ugandan military denies all such allegations of sexual violence and abuse.

“Our soldiers did not get involved in such unprofessional behavior,” said a military spokesman, Brig. Richard Karemire. “We don’t have one” case.

Similarly, the American Special Operations forces partnering with the Ugandans in the fight against the Lord’s Resistance Army denied any “direct knowledge of any sexual misconduct by U.P.D.F. forces,” according to Brig. Gen. Donald C. Bolduc, who commands American Special Operations in Africa.

A United States State Department official said, however, that American diplomats did discuss the allegations with military and civilian leaders in Uganda, who promised that “any soldiers responsible for such acts would be repatriated and prosecuted.”

Over almost three decades, Mr. Kony and his fighters killed more than 100,000 people and abducted more than 20,000 children to use as soldiers, servants or sex slaves, according to the United Nations.

But the Lord’s Resistance Army has withered, to about 100 fighters from a peak of about 3,000. No longer viewing the group as the threat it once was, the Ugandan military said last month that it was withdrawing its entire contingent of about 1,500 soldiers in the Central African Republic. The 150 American soldiers helping in the hunt for Mr. Kony are also standing down.

This region of the Central African Republic is one of the most remote and lawless parts of the country. Surrounded by dense forests, the town of Obo is right at the triple border with South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo — the territory of Mr. Kony’s L.R.A.

Inside the Ugandan camp here, the headquarters for the military’s regional mission against the Lord’s Resistance Army, soldiers cluster around a fire pit and hang their laundry on strings. Broken, rusted and half-disassembled military trucks litter the area.

The women and girls entered the Ugandan headquarters “like it was the most normal thing in the world,” said Lewis Mudge, a researcher for Human Rights Watch who has investigated allegations of sexual violence. “It was a complete culture of impunity where this was completely tolerated and accepted.”

The United Nations defines sexual exploitation as “any actual or attempted abuse of position of vulnerability, differential power or trust, for sexual purposes.” The African Union prohibits any “sexual activities” with children as well as any “sexual favor in exchange for assistance.”

Newsletter Sign Up

Thank you for subscribing.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

View all New York Times newsletters.

Jolie Nadia Ipangba said she was 16 when a Ugandan soldier pursued a relationship with her.

“My father had died, so that’s why I accepted to be with” the soldier, she said. “Because he would support me,” she added. “For me, it was an opportunity.”

Ms. Ipangba, who is now 18, said the soldier told her he was looking for a woman to have a child for him and promised to take care of the mother. However, a month after she got pregnant, he was back home in Uganda.

“After he left, that was it,” she said. “I never heard from him again.”

Under Ugandan law, the Ugandan military conducts the investigations and prosecutes its own soldiers for crimes committed while they are deployed outside Uganda.

Ugandan authorities sent their own team in September 2016 to look into the allegations. No soldier has been charged or prosecuted for sexual crimes, said the spokesman, Brigadier Karemire.

Troops from Uganda are far from the only forces accused of abuse in the country.

Central African Republic, one of the continent’s most vulnerable countries, has been rife with allegations that foreign soldiers sexually exploited its citizens. Peacekeepers from France, Gabon, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, as well as contingents from the European Union and the African Union have all been accused of sexual abuse over the past couple of years, including against children.

The top United Nations human rights official has called the problem of sexual abuse by peacekeepers “rampant.” The former head of the United Nations mission in the country was fired in 2015, after the first allegations.

The security environment in the southeastern Central African Republic contributes to the environment of impunity, said Mr. Daba, the local victims’ advocate.

“There is no law here in Obo,” Mr. Daba said. “There’s no authority. There’s no gendarmes, no police, not even a court. So the U.P.D.F. do what they want.”

Ms. Animbou said she eventually got pregnant with the soldier’s child. He promised to take care of the baby but left the country before she gave birth and has not helped since.

Uganda’s penal code does prohibit abandoning and failing to support children. But Ms. Animbou said she never went to the Ugandan base or the local authorities to report the soldier.

“They don’t want to talk about this, even with the authorities,” said Mr. Daba, adding that some women were threatened by Ugandan soldiers. “The U.P.D.F. said they will do something bad to them — kill them or something else.”

The United Nations and Human Rights Watch found similar evidence of threats of retaliation.

Mr. Daba said it was difficult for the abandoned women to feed their children.

“I don’t have enough clothes or even soap to clean her,” Ms. Ipangba said of her child. “I pray to God to guard me and give me strength to watch over my child because it’s just me who has to take care of her.”

Gladis Koutiyote said she, too, had a child with a Ugandan soldier who promised to marry her. She said some Ugandan soldiers did bring her “a little bit of sugar in a cup and some rice.”

“I used it for just one day and then it was finished,” she said.

The girl who said she was raped in the fields at 13 said she had to drop out of school to take care of her child. She wants the soldier to go to prison and to provide money for the baby’s care. But she said she was not sure she would ever get justice.

She still walks miles to a field to grow beans, manioc and maize to eat. “But I’m scared,” she said. “I worry that he could come for me again.”

Brigadier Karemire, the Ugandan military spokesman, said the Ugandan investigations were finished. He said that no cases of rape or statutory rape were registered here in the Central African Republic, and that there was no plan to support any children left behind. All Ugandan forces will be gone from the Central African Republic within a few weeks.

We’re interested in your feedback on this page. Tell us what you think.