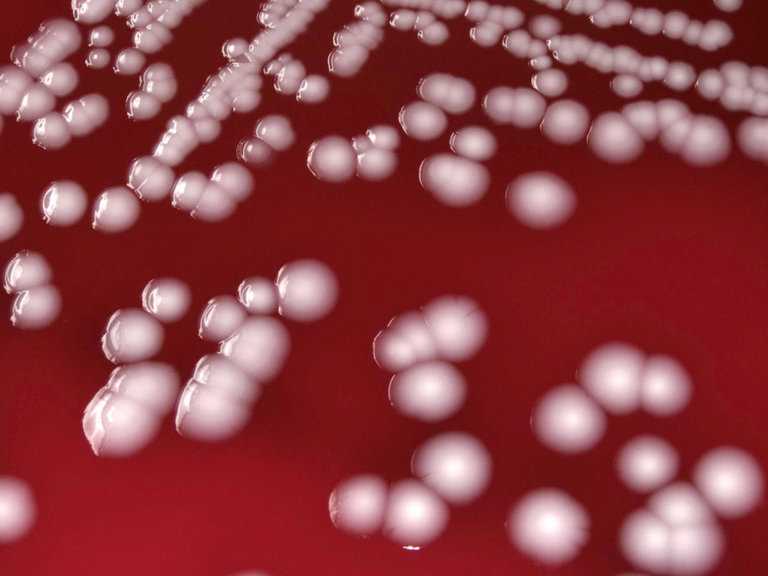

The World Health Organization warned on Monday that a dozen antibiotic-resistant “superbugs” pose an enormous threat to human health, and urged hospital infection-control experts and pharmaceutical researchers to focus on fighting the most dangerous pathogens first.

The rate at which new strains of drug-resistant bacteria have emerged in recent years — prompted by overuse of antibiotics in humans and livestock — terrifies public health experts. Many consider the new strains just as dangerous as emerging viruses like Zika or Ebola.

“We are fast running out of treatment options,” said Dr. Marie-Paule Kieny, the W.H.O. assistant director general who released the list. “If we leave it to market forces alone, the new antibiotics we most urgently need are not going to be developed in time.”

Britain’s chief medical officer, Sally C. Davies, has described drug-resistant pathogens as a national security threat equivalent to terrorism, and Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, the recently retired director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, called them “one of our most serious health threats.”

The World Health Organization warned on Monday that a dozen antibiotic-resistant “superbugs” pose an enormous threat to human health, and urged hospital infection-control experts and pharmaceutical researchers to focus on fighting the most dangerous pathogens first.

The rate at which new strains of drug-resistant bacteria have emerged in recent years — prompted by overuse of antibiotics in humans and livestock — terrifies public health experts. Many consider the new strains just as dangerous as emerging viruses like Zika or Ebola.

“We are fast running out of treatment options,” said Dr. Marie-Paule Kieny, the W.H.O. assistant director general who released the list. “If we leave it to market forces alone, the new antibiotics we most urgently need are not going to be developed in time.”

Britain’s chief medical officer, Sally C. Davies, has described drug-resistant pathogens as a national security threat equivalent to terrorism, and Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, the recently retired director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, called them “one of our most serious health threats.”

Last week, the European Food Safety Authority and European Center for Disease Prevention and Control estimated that superbugs kill 25,000 Europeans each year; the C.D.C. has estimated that they kill at least 23,000 Americans a year. (For comparison, about 38,000 Americans die in car crashes yearly.)

Most of these deaths occur among older patients in hospitals or nursing homes, or among transplant and cancer patients whose immune systems are suppressed. But some are among the young and healthy: A new study of 48 American pediatric hospitals found that drug-resistant infections in children, while still rare, had increased sevenfold in eight years, which the authors called “ominous.”

The W.H.O. report rated research on three pathogens as “critical priority.” They are carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, along with all members of the Enterobacteriaceae family resistant to both carbapenems and third-generation cephalosporins.

(The Enterobacteriaceae family includes familiar names like E. coli and salmonella, which live in human and animal guts and can cause food poisoning, and Yersinia pestis, which causes bubonic plague. Carbapenems and cephalosporins are each “families” of related antibiotics; both break down bacterial cell walls.)

The W.H.O. listed six pathogens as “high” priority. They included methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, better known as MRSA, which is responsible for about a third of “flesh-eating bacteria” infections in the United States. They also included antibiotic-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae, which causes gonorrhea.

The W.H.O.’s third category was “medium priority,” which included drug-resistant versions of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and shigella, all three of which cause common childhood infections. For now, most of those infections are curable, but doctors fear that resistant strains will push out weaker ones.

Tuberculosis was not on the W.H.O.’s list even though lethal drug-resistant strains — known as MDR-TB and XDR-TB — pose a major threat, because there are programs targeted at it.

The C.D.C. released a similar report in 2013, ranking 18 drug-resistant bacteria and fungi in three categories: urgent, serious and concerning.

The two lists have some differences, noted Jean B. Patel, a C.D.C. specialist in drug-resistant bacteria who consulted with the W.H.O. For example, N. gonorrhoeae was a higher priority on the C.D.C. list because it is hard to treat, even though it rarely kills; the W.H.O. list focused more on fatal infections.

The C.D.C. does not consider H. influenzae — better known as Hib — to be as big a threat as the W.H.O. does, she said, because nearly all American babies get Hib shots, which prevent it. In poor countries, according to a 2009 study, more than 300,000 children a year die of Hib-related meningitis or pneumonia.

Some bacteria resistant to all known antibiotics have been found. They are rare and, thus far, usually strike patients whose immune systems are weak. But, once they take hold, they are virtually unstoppable, and victims usually die.

Thank you for subscribing.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

View all New York Times newsletters.

It’s useful for the W.H.O. to set global research priorities because drug-resistant strains are not evenly spread around the world. Some strains are more common on some continents, although jet travel and medical tourism are making most spread worldwide.

Strains can even vary within hospitals.

For example, the antibiotics used in a transplant unit often differ from those used in neonatal intensive care, so different resistant bacteria may circulate, said Dr. William Schaffner, head of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Infants in eastern Tennessee, he said, had more antibiotic-resistant ear infections than those in the state’s western half or in many other states. Doctors there are “exuberant prescribers,” he said, which drives antibiotic resistance.

Resistance to carbapenems, which had been reliable “last line of defense” drugs, has developed recently among pathogens, as a gene first found in India in 2008 — and named NDM for “New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase” — spread around the world.

The latest last-ditch antibiotic to start failing is colistin, which was invented in 1959 but shelved because it caused kidney damage. Chinese pig farmers adopted it and feed nearly 12,000 tons to their pigs each year to speed their growth.

Drug-resistant strains were first found in China in 2015, with a disturbing aspect: the resistance-conferring gene was not in the bacteria’s own DNA but on a plasmid, a small DNA ring that can jump from one bacterial species to another. The Chinese study found it in 21 percent of pigs sampled, and 1 percent of hospitalized humans. The first American patient with it was found last year.

Colistin resistance “sent shock waves through the medical and scientific communities,” Dr. Margaret Chan, the W.H.O.’s director general, said last year. “If we lose colistin, as several experts are predicting, we lose our last medicine for a number of serious infections.”

In the United States, although constant vigilance is crucial, the problem has actually declined in the last decade, said Dr. John Quale, an infectious disease specialist at SUNY Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn who tracks resistance.

In 2008, he said, Medicare stopped reimbursing hospitals for treating catheter-related infections — ones they might have caused. Hospitals became more rigorous about infection control, and that may have cut opportunities for resistant strains to flourish, he said.

The W.H.O. list, Dr. Patel said, will also help a project the W.H.O. began in 2015, the Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System, which seeks to standardize all countries’ efforts to detect resistance and keep records to see how they spread.

“We’re at a tipping point,” Dr. Patel said. “We can take action and turn the tide — or lose the drugs we have.”

We’re interested in your feedback on this page. Tell us what you think.