While fixing my 4-year-old daughter’s bookshelf, I noticed something missing on the glossy covers of her picture books: girls of color. There were talking cars, imaginary creatures and stories about white men, women and children.

I needed to do more than fix the bookshelf; I needed to remedy the contents.

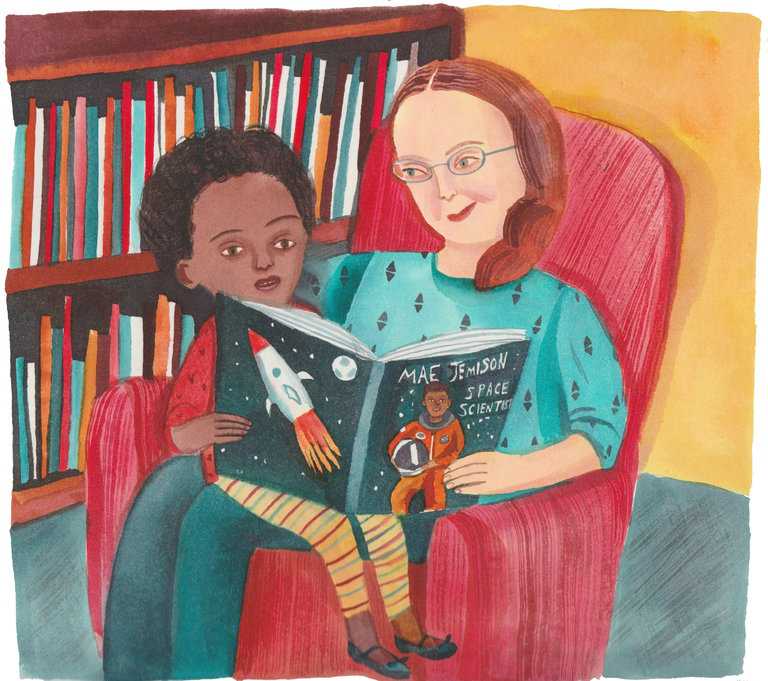

It wasn’t that my daughter never heard stories featuring characters that look like her. I’m a kindergarten teacher, and I often borrow books with diverse characters from both the school and local libraries. But once I noticed the imbalance in our personal collection, I felt the books we actually owned should reflect her. The lack of representation should have been obvious much sooner, but I realized that as a white mother, white privilege afforded me a certain level of oblivion to the racial makeup of our book characters. Part of adopting transracially is learning what to pay attention to. As soon as I was aware of what was missing, I committed myself to filling our bookshelves with stories about smart, talented, strong black females.

In the mid 1960s, the children’s book editor Nancy Larrick found that the publishing houses putting out the most children’s books containing black characters still featured them less than 5 percent of the time (and not necessarily main characters or positive images). Ms. Larrick was among the first in children’s publishing to say that it was a problem for black children to learn about their world through books that do not represent them.

The diversity gap

in children’s publishing persists today. Of children’s books published from 1994 to 2014, an average of 10 percent featured multicultural content, though that may be slowly increasing: The 2014 rate reached 14 percent. The campaign We Need Diverse Books was established in 2014 to advocate for more diverse representation in children’s literature. And in 2015, at age 11, Marley Dias started the Twitter hashtag #1000blackgirlbooks. Frustrated by the homogeneity of stories she read in class, Marley collected books featuring black girls to benefit underprivileged students.

While fixing my 4-year-old daughter’s bookshelf, I noticed something missing on the glossy covers of her picture books: girls of color. There were talking cars, imaginary creatures and stories about white men, women and children. I started counting and discovered that only 4 percent of our books featured minorities as main characters, and only one was a black girl like my daughter.

I needed to do more than fix the bookshelf; I needed to remedy the contents.

It wasn’t that my daughter never heard stories featuring characters that look like her. I’m a kindergarten teacher, and I often borrow books with diverse characters from both the school and local libraries. But once I noticed the imbalance in our personal collection, I felt the books we actually owned should reflect her. The lack of representation should have been obvious much sooner, but I realized that as a white mother, white privilege afforded me a certain level of oblivion to the racial makeup of our book characters. Part of adopting transracially is learning what to pay attention to. As soon as I was aware of what was missing, I committed myself to filling our bookshelves with stories about smart, talented, strong black females.

In the mid 1960s, the children’s book editor Nancy Larrick found that the publishing houses putting out the most children’s books containing black characters still featured them less than 5 percent of the time (and not necessarily main characters or positive images). Ms. Larrick was among the first in children’s publishing to say that it was a problem for black children to learn about their world through books that do not represent them.

The diversity gap in children’s publishing persists today. Of children’s books published from 1994 to 2014, an average of 10 percent featured multicultural content, though that may be slowly increasing: The 2014 rate reached 14 percent. The campaign We Need Diverse Books was established in 2014 to advocate for more diverse representation in children’s literature. And in 2015, at age 11, Marley Dias started the Twitter hashtag #1000blackgirlbooks. Frustrated by the homogeneity of stories she read in class, Marley collected books featuring black girls to benefit underprivileged students.

The education professor Rudine Sims Bishop uses the metaphor of windows, sliding glass doors and mirrors to illustrate why diverse literature is so important. Books can be windows into worlds previously unknown to the reader; they open like sliding glass doors to allow the reader inside. But books can also be mirrors. When books reflect back to us our own experiences, when scenes and sentences strike us as so true they are anchors mooring us to the text, it tells readers their lives and experiences are valued. When children do not see themselves in books, the message is just as clear.

Of course, my daughter relates to characters for many reasons that have nothing to do with race. She identifies with Sal’s insatiable hunger for blueberries and Harold’s love of his purple crayon. Enamored by wild things at wild rumpuses, she dressed as Max for Halloween. In Louise Rosenblatt’s transactional theory of reading, individuals bring their own experiences to a text to understand and draw meaning from it. There are multiple ways to identify with a text and racially is only one. But if a child’s race or ethnicity is underrepresented in books, it says something about how those pieces of their identities are valued.

My daughter notices mirrors, not just in books, but all around her. Watching the ballerina Michaela DePrince, who lived through the civil war in Sierra Leone, perform in “The Nutcracker,” she exclaimed over the hushed audience, “I like the brown girl!” She notices equally when groups are underrepresented in certain roles. I once asked her to give her train ticket to the conductor and she replied, “That’s not a conductor, that’s a lady!” It was her first time seeing a female conductor.

For our updated bookshelves, I envisioned black female characters in many different roles. I wanted fairy tales and nursery rhymes; books about discrimination, civil rights, and social justice; fiction set in rural and urban places, in the United States and overseas; biographies of black female role models, and stories of black girls doing everyday things. I would need to shop.

But on a trip to a bookstore in New Jersey, where I lived at the time, not one picture book on display featured a female of color. Outward facing covers showed many white children, animals and personified objects, a handful of diverse boys, but no black girls. I thumbed through the shelves, pulling out spines one by one without luck.

“I’m looking for picture books featuring African or African-American females,” I told a saleswoman.

Thank you for subscribing.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

View all New York Times newsletters.

She didn’t know any titles offhand and said, “You can’t look up topics like that,” when I asked her to search her computer.

I looked up names online of diverse characters, authors and illustrators I knew as a teacher. I read reviews. I jotted down names of famous black women and searched for children’s literature featuring them. I checked winners of the Coretta Scott King Book Awards and those from the foundation started by Ezra Jack Keats, who is credited with breaking ground in 1962 with one of the first multicultural picture books, “The Snowy Day.”

The effects of incorporating these books into our collection were immediate. When my daughter saw a spaceship in an ad she said, “Oh! Mae did that,” referencing Mae Jemison, the first African-American woman to travel in space.

She told me that she was like Wangari Maathai, the Nobel Peace Prize winner, because, “When the trees were broken she planted new ones, and I love trees.”

My daughter befriended new characters. Jamaica from suburban America. Jamela from urban South Africa. Elizabeti in rural Tanzania. She loves their relatable problems: hurt feelings, accidental messes, losing a beloved doll.

I had set out to simply reattach the loose brackets of my daughter’s bookshelf. But I ended up installing mirrors, a much more needed repair.

We’re interested in your feedback on this page. Tell us what you think.