BEIJING — Qian Qichen, an imperturbable Chinese diplomat who as foreign minister and vice premier steered his country on a pragmatic course through the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union and bitter quarrels with the United States, died here on Tuesday.

He was 89.

Official Chinese news reports announced Mr. Qian’s death but did not give a cause.

Mr. Qian, whose full name is roughly pronounced chee-en chee-chen, had mostly stayed out of the public eye in recent years, but on Thursday his death was mourned on the front page of People’s Daily, the Communist Party’s main newspaper — a sign of the deep imprint he made in shaping a muted, unsentimental policy after the Soviet bloc fell apart in 1991 and in chipping away at China’s isolation from the West in the years after 1989.

“Deng Xiaoping was the architect of China’s pragmatic foreign policy, but Qian Qichen was the diplomat who carried it out,” said Susan L. Shirk, who worked with Mr. Qian when she was a deputy assistant secretary of state under President Bill Clinton and is now a professor at the University of California, San Diego.

Mr. Qian’s tough yet phlegmatic manner underwent its biggest test when the United States and other Western nations bridled with revulsion after Deng, the party’s most powerful elder, ordered soldiers in June 1989 to crush pro-democracy protests that had engulfed Beijing and other Chinese cities. Hundreds of civilians died in the gunfire and the chaos on roads leading to Tiananmen Square.

BEIJING — Qian Qichen, an imperturbable Chinese diplomat who as foreign minister and vice premier steered his country on a pragmatic course through the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union and bitter quarrels with the United States, died here on Tuesday. He was 89.

Official Chinese news reports announced Mr. Qian’s death but did not give a cause.

Mr. Qian, whose full name is roughly pronounced chee-en chee-chen, had mostly stayed out of the public eye in recent years, but on Thursday his death was mourned on the front page of People’s Daily, the Communist Party’s main newspaper — a sign of the deep imprint he made in shaping a muted, unsentimental policy after the Soviet bloc fell apart in 1991 and in chipping away at China’s isolation from the West in the years after 1989.

“Deng Xiaoping was the architect of China’s pragmatic foreign policy, but Qian Qichen was the diplomat who carried it out,” said Susan L. Shirk, who worked with Mr. Qian when she was a deputy assistant secretary of state under President Bill Clinton and is now a professor at the University of California, San Diego.

Mr. Qian’s tough yet phlegmatic manner underwent its biggest test when the United States and other Western nations bridled with revulsion after Deng, the party’s most powerful elder, ordered soldiers in June 1989 to crush pro-democracy protests that had engulfed Beijing and other Chinese cities. Hundreds of civilians died in the gunfire and the chaos on roads leading to Tiananmen Square.

In Congress there were demands for harsh sanctions, but President George Bush, not wanting to risk a total rupture with China over the violence, sent his national security adviser, Brent Scowcroft, to Beijing for talks. In their meetings, at first held in secret, Mr. Scowcroft sparred with Mr. Qian over how to improve relations.

“You have your difficulties, and we have ours,” Mr. Qian told Mr. Scowcroft, according to Mr. Qian’s memoirs, which were published in Chinese in 2003 and in English in 2006. “You’re looking for a solution, and we’re also looking for one.”

Mr. Scowcroft, in a talk in 2006, said that although tensions between the two nations had persisted, “in negotiating principally with Qian Qichen, we came up with a road map to renormalize our relations.”

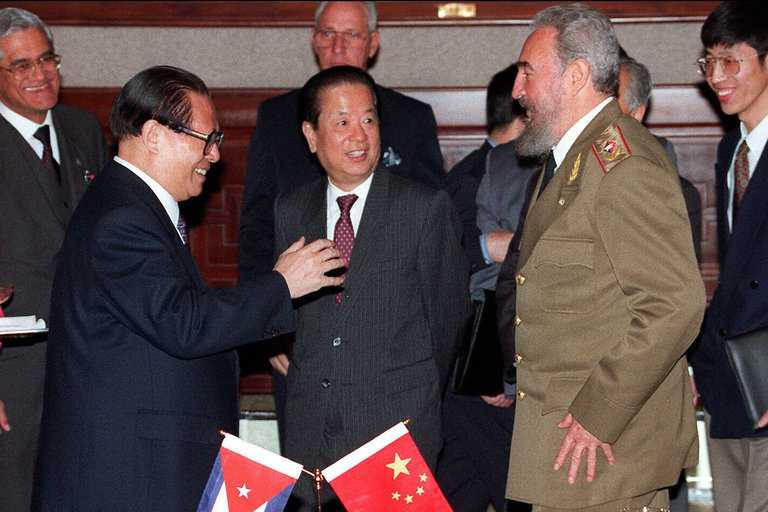

Mr. Qian so won the trust of Deng and President Jiang Zemin that he was elevated to vice premier in 1993 and into the Politburo, or Political Bureau, a council of 25 senior officials, in 1998. It was a rare feat for a career diplomat, one that has not been matched by any succeeding foreign minister.

“The fact that he rose to become both vice premier and a Political Bureau member is a mark of the high esteem in which he was held by Chinese leaders,” Robert L. Suettinger, a China researcher in Washington, said in an email, adding that Mr. Qian “was able to guide Jiang Zemin and others out of international isolation after Tiananmen.”

Mr. Suettinger was director of Asian affairs on the National Security Council under President Clinton when he met Mr. Qian, whom he described as “always well-informed, consistently knowledgeable, never unsure of his brief.”

Mr. Qian began his career prepared for a very different world; at the time, it seemed that China and the Soviet Union had formed an ironclad alliance and that the United States would be their perpetual foe.

He was born on Jan. 5, 1928, in Tianjin, a northern Chinese port city, but traced his roots more than 700 miles to the south, to Jiading, now a district of Shanghai. His ancestors included a famed Qing-era scholar.

As a student in pre-revolutionary Shanghai, Mr. Qian was drawn into underground activism for the Communist Party. He joined the party in 1942, seven years before Mao Zedong declared the creation of the People’s Republic of China.

Chinese reports about Mr. Qian’s death gave few details about his background and family, although a son, Qian Ning, wrote an admiring book about the United States based on his experiences as a student at the University of Michigan.

Mr. Qian was sent to study in the Soviet Union in 1954 after spending several years as a journalist and party operative. The next year he was given a junior post in the Chinese embassy in Moscow. There, for seven years, he watched the relationship between Beijing and the Kremlin crumble.

Newsletter Sign Up

Thank you for subscribing.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

View all New York Times newsletters.

Mao had looked to the Soviet Union as an ideological soul mate and source of expertise, but relations soured over doctrinal rifts and Chinese resentment of Russian dominance.

After he returned to China in 1962, Mr. Qian continued his way up the foreign policy ladder. But like many officials he was sidelined by the anarchic Cultural Revolution that Mao unleashed in 1966. Mr. Qian was sent to a “cadre school” for re-educating officials before being called back into diplomatic service in 1972.

After Mao’s death, in 1976, Mr. Qian embraced a push by Deng and other leaders to open China up to the world. He was promoted to foreign minister in 1988, when China’s efforts to build bridges with the West and the Soviet Union seemed to be succeeding. But in little over a year, the carnage at Tiananmen Square and the fall of the Soviet bloc threw China’s diplomatic progress into doubt.

As Communism dissolved in Eastern Europe, some Chinese officials wanted Beijing to step forward as a bolder ideological rival to the United States. But Mr. Qian supported Deng’s policy of a low-profile, practical foreign policy that would allow China to focus on economic growth and core territorial issues, like the one with Taiwan. Deng called it “biding our time and nurturing our strength.”

Explaining that policy in 1995, Mr. Qian said: “The only thing is to focus on doing our own tasks. No matter how international circumstances change, we must hold unwaveringly onto economic development as the focus.”

Throughout the 1990s, Mr. Qian led China’s effort to end its ostracism by the West. He helped draw Japan closer to China, opened diplomatic relations with South Korea, normalized ties with Indonesia, wooed Russia and other post-Soviet states, and looked toward improving ties with Washington.

In 1990, seeking a compromise to end hostilities after Iraq invaded Kuwait, he visited Baghdad for talks with President Saddam Hussein, who asked him whether he thought the United States would really go to war.

“I told him that a great power that has assembled dozens of armies does not back away without a fight unless it had achieved its goal,” Mr. Qian wrote in his memoirs.

Throughout the 1990s, however, he also skirmished with American diplomats over Chinese missile sales to Pakistan, suppression of dissent in China and sanctions on trade with China. China was infuriated when, in 1995, the Clinton administration, pressed by Congress, decided to allow Lee Teng-hui, the president of Taiwan, to visit Cornell University.

The White House described Mr. Lee’s visit as a private one, but China regards Taiwan as an illegitimate breakaway province and denounced the visit as an attempt by Mr. Lee to end its diplomatic isolation. The crisis spilled into 1996, when China fired missiles near Taiwan before the island’s elections.

“China has never committed itself to abandoning the use of force for reunification” with Taiwan, Mr. Qian warned in an hourlong news conference.

Mr. Qian stepped down as foreign minister in 1998 and retired from his other high posts in 2003. Unlike some retired Chinese diplomats, he did not comment publicly as his country’s foreign policy grew more pugnacious in recent years, especially under President Xi Jinping.

Mr. Qian “never berated Western counterparts for effect, as some of his successors did,” Professor Shirk, at the University of California, said. Unlike his weaker successors, she added, Mr. Qian also “appeared to have the authority to make concessions, when necessary, to get agreements.”

We’re interested in your feedback on this page. Tell us what you think.