The last few months, especially since the Chibok girls’ abduction, have left President Goodluck Jonathan’s image seriously battered and in need of repair, writes Financial Times

Few African heads of state have experienced a drubbing at the hands of traditional and social media quite like Nigeria’s President Goodluck Jonathan. In many African countries a degree of deference to the office of the head of state persists.

But in the 56 days since Boko Haram extremists abducted more than 250 school girls in the country’s remote northeast, Nigerian commentators have seized on his government’s chaotic response to portray Mr Jonathan as weak and incapable of tackling the debilitating corruption around him.

The former zoology lecturer, whose humble roots and non-combative style were welcomed when he became president in 2010, is now the butt of comedy skits. The most withering is a puppet show that caricatures him as a small-town politician, surrounded by sycophants, as poorly advised at a national level as he is clueless on the international stage.

It is a reflection of the country’s politics that the evident unease – at least among elites – about Mr Jonathan’s capacity as a leader will not necessarily be the deciding factor in general elections scheduled for next February.

Rather, politicians from the ruling party and the opposition are using the insurgency being waged by Boko Haram to capitalise on the historic cleavage between the country’s predominantly Muslim north and mostly Christian south. This is setting the stage for what could be the most viscerally divisive contest since the end of army rule in 1999.

Ethnic and religious considerations have long been a dominant factor in Nigerian elections. Northern politicians have been clamouring for their turn back at the top ever since Mr Jonathan, a Christian from the oil-producing Niger delta, consolidated his ascent to power at 2011 elections following the death of his northern Muslim predecessor, Umaru Yar’Adua.

Despite the enormous powers vested in the presidency, Mr Jonathan has struggled to appear in charge in the face of multiplying crises. In the latest blow to his authority, Lamido Sanusi, the fiercest critic of his government’s record on corruption whom he ousted as governor of the central bank, has been appointed as emir of Kano, the second highest Islamic authority in the country.

Daily protests at the government’s as-yet-ineffectual efforts to free the abducted girls have united men and women from across the country, albeit in small numbers. The bombings and massacres carried out by the terrorist group have otherwise heightened religious tension and eroded public confidence in the capacity of the security forces to contain any further breakdown in law and order.

“Everyone should be mindful that Nigeria is in such a precarious position,” says Hadiza Bala-Usman, an opposition activist and one of the organisers of the protest campaign “#bringbackourgirls”.

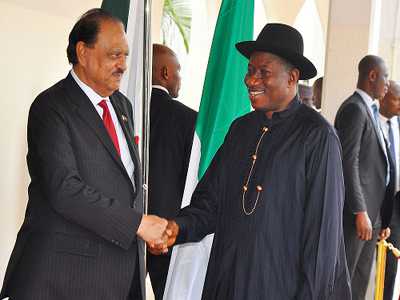

In recent pronouncements, Mr Jonathan has attempted to rally the nation. General Muhammadu Buhari, a former military head of state who won much of the northern Muslim vote as a presidential candidate in 2011 polls, has also sought to rise above the fray.

“We are in a very serious situation where the country should be put first. It is Nigeria against Boko Haram and all those on our side must make sure terrorism is defeated,” he said.

Others are prepared to point fingers.

Olusegun Obasanjo, the former head of state once instrumental in Mr Jonathan’s rise, is now among his strongest critics. He told the Financial Times that the president initially failed to respond to the girls’ abduction because he believed it was concocted as an “attack against him personally” and was part of a broader northern political conspiracy. Many of Mr Jonathan’s supporters hold similar views.

The ruling People’s Democratic party has had no qualms about playing on these fears, portraying the main opposition coalition, the All Progressives Congress, as driven by a Muslim fundamentalist agenda despite its broad reach across ethnic and religious divides.

In a statement last week, Olisa Metuh, the PDP’s national publicity secretary, described the APC as “bloodthirsty, religious and ethnic bigots”.

“Unfortunately what the government has done is to portray everyone who questions governance as a potential sympathiser (of Boko Haram),” said Obi Ezekwisili, a Christian former education minister and World Bank’s vice-president for Africa who is a vocal campaigner for the abducted girls.

The electoral battle lines are still forming with politicians shifting allegiances in anticipation of the polls.

Mr Jonathan has yet to make explicit whether he will contest the election. But several new appointments and the defection to the opposition of many of his most vocal opponents have consolidated his position ahead of primaries later this year. His command of state resources still makes him the man to beat.

APC members believe the support they have in the most populous southwestern and northern states will make it difficult for the ruling party to win a free and fair election. But much will depend on who the coalition chooses as its presidential candidate, and whether it can maintain the loyalty of heavyweight contenders who are passed over.

“What there is now is a vacuum of governance the likes of which we have not seen for a long time,” says a senior western official monitoring the turmoil, who warns there is no guarantee that Nigeria’s elites will close ranks and muddle through the crisis as they have in the past.

Ms Ezekwisili puts it another way: “We need to define a new set of values that govern us,” she says.