Supported by Live Nation Rules Music Ticketing, Some Say with Threats

In 2010, when the Justice Department allowed the two most dominant companies in the live music business — Live Nation and Ticketmaster — to merge, many greeted the news with dread.

Live Nation was already the world’s biggest concert promoter. Ticketmaster had for years been the leading ticket provider. Critics warned that the merger would create an industry monolith, one capable of crippling competitors in the ticketing business.

Federal officials tried to reassure the skeptics. They pointed to a consent decree, or legal settlement, they had negotiated as part of the merger approval. Its terms were strict, they said: it would boost competition and block monopolistic behavior by the new, larger Live Nation.

“There will be enough air and sunlight in this space for strong competitors to take root, grow and thrive,” said the country’s top antitrust regulator, Assistant Attorney General Christine A. Varney. And she went further, suggesting that reduced ticket service fees, even lower ticket prices, might be on the horizon.

Continue reading the main story

But eight years after the merger, the ticketing business remains dominated by Live Nation and its operations now extend into nearly every aspect of the concert world.

Ticket prices are at all-time highs. Service fees are far from reduced. And Ticketmaster, now part of the Live Nation empire, still tickets 80 of the top 100 arenas in the country. No other company has more than a handful. No competitor has risen to challenge its pre-eminence.

Now Department of Justice officials are looking into serious accusations about Live Nation’s behavior in the marketplace.

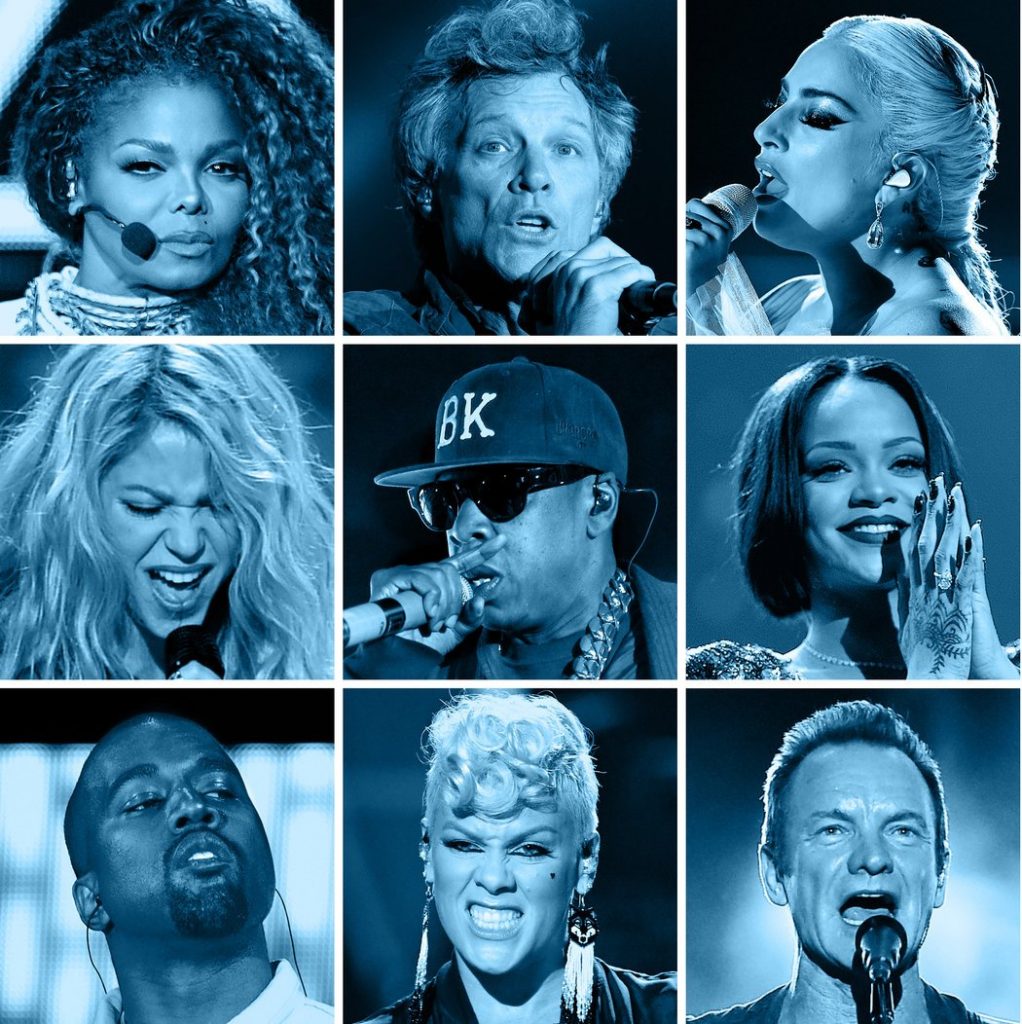

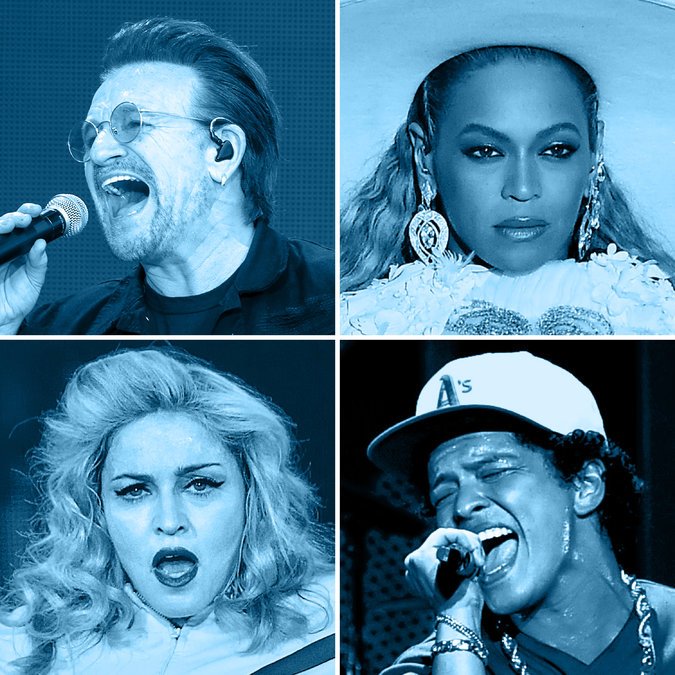

They have been reviewing complaints that Live Nation, which manages 500 artists, including U2 and Miley Cyrus, has used its control over concert tours to pressure venues into contracting with its subsidiary, Ticketmaster. The company’s chief competitor, AEG, has told the officials that venues it manages that serve Atlanta, Salt Lake City, Oakland, Minneapolis, Louisville and Las Vegas, were told they would lose valuable shows if Ticketmaster was not used as a vendor, a possible violation of antitrust law.

Continue reading the main story

In the Atlanta case, the complaint stems from a 2013 tour by the band Matchbox Twenty. Live Nation bypassed the Gwinnett Center, a popular arena outside the city, for another venue in town.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Gwinnett’s booking director, Dan Markham, worried his venue was being punished, according to emails he wrote at the time. The center had just replaced Ticketmaster with a service controlled by AEG.

“Don’t abandon Gwinnett,” he wrote to a Live Nation talent coordinator. “If there’s an issue or issues let’s address.”

“Issue?” the Live Nation coordinator wrote back. “Three letters. Can you guess what they are?”

Live Nation says that, no matter what its employee wrote, the decision to bypass the center was not punitive. The other venue was managed by Live Nation and simply fit more people. But the following year, Live Nation cut the number of tours it brought to Gwinnett in half, from 4 to 2.

Live Nation described the drop as a routine fluctuation. But Mr. Markham later said in an email that he had expected the drop-off because Live Nation “warned us that they would put us in a literal boycott.”

AEG provided the New York Times with copies of those emails, and others, to support its account of threats.

“What happened in Atlanta is just one example of what has been occurring much more broadly,” said Ted Fikre, the chief legal officer for AEG.

Live Nation officials say they never threaten or retaliate. They dismissed the complaints as tactical, deliberate mischaracterizations by AEG.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

“You have a disgruntled competitor that is trying to explain their loss around the boogeyman that there were threats made that nobody can document,” said Daniel M. Wall, Live Nation’s antitrust lawyer.

The bloodletting between Live Nation and AEG has grown fierce in recent years and rippled through the industry. Last month, another of Mr. Wall’s clients, the heavy-metal icon Ozzy Osbourne, sued AEG on antitrust grounds, saying that it tried to bar him from playing its O2 arena in London, unless he played its Staples Center in Los Angeles.

AEG said its policy was a response to Live Nation’s steering concerts to its Los Angeles rival, the Forum.

The Justice Department’s inquiries into possible antitrust violations have gone beyond the bitter rivalry, with regulators in the past year looking into reports of Live Nation threats at venues that AEG does not manage: at the H-E-B Center outside Austin, Tex.; and at Boston’s TD Garden, according to executives familiar with the federal review.

Justice officials declined to comment on the status of their inquiries. Several of the venue owners have denied the accounts of threats reported by others.

The inquiries come as Justice officials review two more proposed mergers of huge companies — AT&T with Time Warner, and the Walt Disney Company with 21st Century Fox. In discussing those proposals, the department’s new antitrust chief has pointed to the Live Nation deal and several other mergers as problematic because, he said, they relied too much on the federal government’s ability to police corporate behavior.

“Even if we wanted to do that, we often don’t have the skills or the tools to do so effectively,” Assistant Attorney General Makan Delrahim said in a speech last November.

Beau Buffier, the chief of the New York Attorney General’s Antitrust Bureau, was blunter in assessing whether the government had done enough to ensure a vital ticketing marketplace.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

“The Consent Decree was supposed to prevent Live Nation from using its strength in live entertainment to foreclose competition in ticketing,” said Mr. Buffier. “But it is now widely seen as the poster child for the problems that arise when enforcers adopt these temporary fixes to limit the anticompetitive effects of deeply problematic vertical mergers.”

Multiple Incomes

The live music business has long operated as an ecosystem where multiple parties work together to put on a show.

Promoters front the money for a concert or tour and take on the greatest risk.

Talent agents and managers negotiate artists’ fees.

Venues rent space and hire ticketing companies to handle their events.

These were long separate fiefs. But Live Nation now operates in all of them, so it’s the rare music fan who does not run into the company somewhere in any concert-going experience.

It operates more than 200 venues worldwide. It promoted some 30,000 shows around the world last year and sold 500 million tickets. Its portfolio of acquisitions since the merger includes the Lollapalooza and Bonnaroo festivals, promoters from Idaho to Sweden, and a string of European and American ticketing companies.

It also draws more fire from music fans than any other company, in large part because it is blamed — unfairly in many respects — for skyrocketing ticket prices and the size of those much-maligned ticket service fees, both costs it only partly influences.

Though the price of tickets has soared, that trajectory predates the merger and is driven by many factors, including artists’ reliance on touring income as record sales have plummeted.

Alan B. Krueger, a professor of economics and public policy at Princeton University, said that fan demand was the primary force behind higher prices and the money was drawing a broader array of acts to the stage.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Live Nation typically locks up much of the best talent by offering generous advances to artists and giving them a huge percentage of the ticket revenue from the door.

Why? Because it can afford to. It has so many other related revenue streams on which to draw: sponsorships for the tour, concessions at venues, and, most of all, ticket fees. The fees supply about half of Live Nation’s earnings, according to company reports.

Ticketmaster said it no longer sets the final fee. It just negotiates a set per-ticket charge. The rest of the fee is added on by the venues and sometimes promoters too. Yet at many concerts Live Nation is not just the ticket seller, but also the promoter, the venue operator or even the artist’s manager, with an opportunity to collect at every juncture.

Continue reading the main story Read the Original Article