More than a quarter of a million Somali refugees got a huge break on Thursday.

A Kenyan judge ruled that the Kenyan government’s contentious plan to close Dadaab, the world’s largest refugee camp, was “illegal” and “discriminatory,” and that the refugees could not be forcefully relocated.

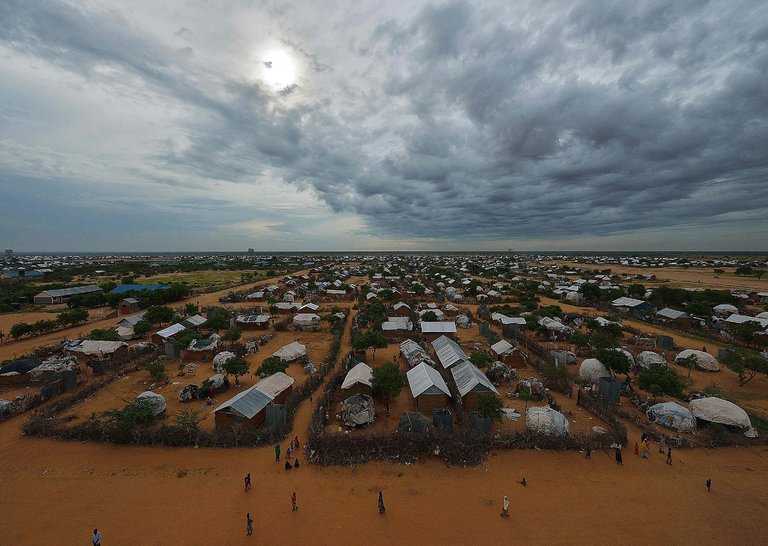

For years, Kenya has threatened to shut the sprawling camp, a crowded, sweltering realm near Kenya’s border with Somalia that has been a refuge for desperate people since Somalis began fleeing to Kenya in 1991, when their country was plunged into civil war.

The government has said the camp is a breeding ground for Islamist terrorists, though the evidence is mixed for how central it really is to Kenya’s terrorism problem, which has claimed hundreds of lives in recent years.

The vast majority of refugees who live in Dadaab are Somalis, too scared to return home to a nation plagued by war, famine, chaos, poverty and disease.

On Thursday, Judge John Mativo of Kenya’s High Court, the equivalent of an American Federal District Court, ruled that the government’s plan to close the camp “specifically targeting Somali refugees is an act of group persecution, illegal, discriminatory and therefore unconstitutional.”

The judge also ordered the Kenyan government to reinstate its refugee department, which the government essentially closed last year.

In May, Kenya announced it was serious about closing Dadaab, though it has since missed several self-imposed deadlines. Diplomats, United Nations agencies and human rights groups have told the Kenyans that forcing the refugees to return to Somalia would be a violation of international law.

Kenya’s foreign donors, including the United States, have threatened to withhold payments if the government kicks out the refugees. That has left Kenya in a tight spot: Relocating hundreds of thousands of people would not be cheap.

Thank you for subscribing.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

View all New York Times newsletters.

Few say they believe Dadaab’s future is settled. Within hours of the ruling, the Kenyan government vowed to appeal, arguing that the situation in Somalia had improved and the refugees could return.

It is unclear whether the Kenyan government will follow the court order. Though Kenya’s judiciary is considered strong and independent, the president has enormous power and Kenyan security forces routinely violate the rights of Somali refugees.

Still, the pressure is growing to do something about Dadaab. Aid officials, who have sharply criticized repatriation, admit that the current situation is untenable.

“Kenya and the international community must work toward finding alternative solutions for refugees, including local integration options,” said Muthoni Wanyeki, an Amnesty International regional director.

More than 9,000 Somali refugees were resettled in the United States last fiscal year, many coming from Dadaab. But a recent change in United States policy could threaten that trend.

President Trump signed an executive order last month barring Somalis from traveling to the United States. Over the past two weeks, scores of refugees have been bused back and forth between Dadaab and Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, as the United States’ refugee policy is argued in American courts.

More than a quarter of a million Somali refugees got a huge break on Thursday.

A Kenyan judge ruled that the Kenyan government’s contentious plan to close Dadaab, the world’s largest refugee camp, was “illegal” and “discriminatory,” and that the refugees could not be forcefully relocated.

For years, Kenya has threatened to shut the sprawling camp, a crowded, sweltering realm near Kenya’s border with Somalia that has been a refuge for desperate people since Somalis began fleeing to Kenya in 1991, when their country was plunged into civil war.

The government has said the camp is a breeding ground for Islamist terrorists, though the evidence is mixed for how central it really is to Kenya’s terrorism problem, which has claimed hundreds of lives in recent years.

The vast majority of refugees who live in Dadaab are Somalis, too scared to return home to a nation plagued by war, famine, chaos, poverty and disease.

On Thursday, Judge John Mativo of Kenya’s High Court, the equivalent of an American Federal District Court, ruled that the government’s plan to close the camp “specifically targeting Somali refugees is an act of group persecution, illegal, discriminatory and therefore unconstitutional.”

The judge also ordered the Kenyan government to reinstate its refugee department, which the government essentially closed last year.

In May, Kenya announced it was serious about closing Dadaab, though it has since missed several self-imposed deadlines. Diplomats, United Nations agencies and human rights groups have told the Kenyans that forcing the refugees to return to Somalia would be a violation of international law.

Kenya’s foreign donors, including the United States, have threatened to withhold payments if the government kicks out the refugees. That has left Kenya in a tight spot: Relocating hundreds of thousands of people would not be cheap.

Thank you for subscribing.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

View all New York Times newsletters.

Few say they believe Dadaab’s future is settled. Within hours of the ruling, the Kenyan government vowed to appeal, arguing that the situation in Somalia had improved and the refugees could return.

It is unclear whether the Kenyan government will follow the court order. Though Kenya’s judiciary is considered strong and independent, the president has enormous power and Kenyan security forces routinely violate the rights of Somali refugees.

Still, the pressure is growing to do something about Dadaab. Aid officials, who have sharply criticized repatriation, admit that the current situation is untenable.

“Kenya and the international community must work toward finding alternative solutions for refugees, including local integration options,” said Muthoni Wanyeki, an Amnesty International regional director.

More than 9,000 Somali refugees were resettled in the United States last fiscal year, many coming from Dadaab. But a recent change in United States policy could threaten that trend.

President Trump signed an executive order last month barring Somalis from traveling to the United States. Over the past two weeks, scores of refugees have been bused back and forth between Dadaab and Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, as the United States’ refugee policy is argued in American courts.

We’re interested in your feedback on this page. Tell us what you think.