Supported by

Health

Is This Tissue a New Organ? Maybe. A Conduit for Cancer? It Seems Likely.

Researchers have made new discoveries about the in-between spaces in the human body, and some say it’s time to rewrite the anatomy books.

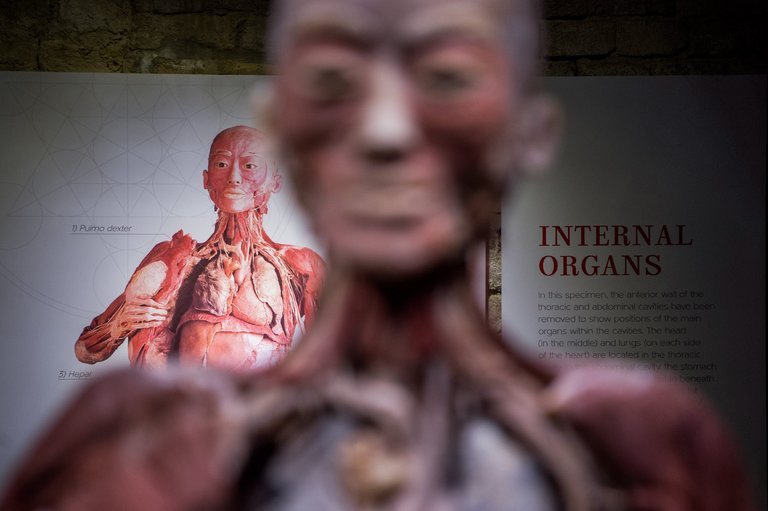

A study published in Scientific Reports this week described a fluid-filled, 3-D latticework of collagen and elastin connective tissue that can be found all over the body, in or near our lungs, skin, digestive tracts and arteries.

It’s a hard thing to describe, and the New York University School of Medicine did it in several ways in a news release on Tuesday: a “series of spaces,” a “highway of moving fluid” and “a previously unknown feature of human anatomy.”

It said the study’s authors referred to the system as “an organ in its own right,” though not all researchers agree with that characterization.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

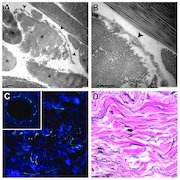

Images captured by transmission electron microscopy show blobs of collagen bundles and long, snaky cells. It looks fluid — something that ebbs and flows, like the ocean. It is similarly underexplored.

This network could act as shock absorber for other parts of the body, researchers said. It also seems to be a conduit for fluids to enter the lymphatic system, which means it could spread diseases through the body — including by helping cancers to metastasize.

Continue reading the main story

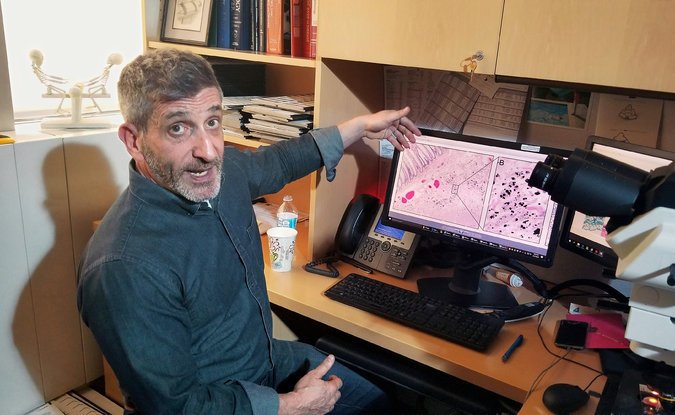

“We have never understood the mechanism of how that happens,” said Dr. Neil Theise, a pathologist and professor at the New York University School of Medicine and a senior author of the published paper. “Now we have the ability. If we figure out the mechanism, we can figure out how to interfere with it.”

The paper referred to this “widespread, macroscopic, fluid-filled space within and between tissues” as the interstitium (pronounced inter-STISH-um).

The research began in 2014 when two endoscopists and gastroenterology experts, Petros Benias and David Carr-Locke, were using a newer imaging technology to examine a patient’s bile duct at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital in Manhattan.

The probe-based technology essentially allows doctors to examine live tissue at a microscopic level inside the body and in real time. They captured images of fluid-filled cavities that they wanted to understand better, so they took them to Dr. Theise.

Doctors and researchers had been looking at this tissue for years, often by removing samples from the body to examine under a microscope, but that process collapsed the latticework into something that looked crackly and dense.

“Several things happen to a surgical specimen when you take it out of the body. It completely structurally changes, and all the water is lost,” Dr. Benias said. “You’re missing a lot of the story there, and that’s the problem.”

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

But the newer technology revealed an interstitial network that was “extensive” and more than worthy of being considered an organ, he added, calling it “an entire system that is interfacing between the vascular system and the lymphatic.”

Newsletter Sign Up

Continue reading the main story

Please verify you're not a robot by clicking the box.

Invalid email address. Please re-enter.

You must select a newsletter to subscribe to.

Sign Up You agree to receive occasional updates and special offers for The New York Times's products and services.

Thank you for subscribing.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

View all New York Times newsletters.

- See Sample

- Manage Email Preferences

- Not you?

- Privacy Policy

- Opt out or contact us anytime

James M. Williams, the director of the Human Anatomy Laboratory at Rush University, was not involved in the study but said the researchers’ work and the technology they used to see the interstitium was exciting and could change the way doctors treat cancers and other diseases.

But the words “new organ” attached to the study were a distraction, he said.

“The only new organs that are being made these days are those that appear onstage and make music,” Dr. Williams said, adding that he was looking forward to delving deeper into the research.

So is Dr. Benias, who said more study of the interstitium could lead to breakthroughs in cancer treatment. He added that the study involved clinicians, pathologists, bioengineers and others.

“A lot of research happens in a bubble, unfortunately,” he said. “People miss the forest for the trees.”

Continue reading the main story Read the Original Article