A Strong Case Against a Pesticide Does Not Faze E.P.A. Under Trump

Some of the most compelling evidence linking a widely used pesticide to developmental problems in children stems from what scientists call a “natural” experiment.

Though in this case, there was nothing natural about it.

Chlorpyrifos (pronounced klor-PYE-ruh-fahs) had been used to control bugs in homes and fields for decades when researchers at Columbia University began studying the effects of pollutants on pregnant mothers from low-income neighborhoods. Two years into their study, the pesticide was removed from store shelves and banned from home use, because animal research had found it caused brain damage in baby rats.

Pesticide levels dropped in the cord blood of many newborns joining the study. Scientists soon discovered that those with comparatively higher levels weighed less at birth and at ages 2 and 3, and were more likely to experience persistent developmental delays, including hyperactivity and cognitive, motor and attention problems. By age 7, they had lower IQ scores.

The Columbia study did not prove definitively that the pesticide had caused the children’s developmental problems, but it did find a dose-response effect: The higher a child’s exposure to the chemical, the stronger the negative effects.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

That study was one of many. Decades of research into the effects of chlorpyrifos strongly suggests that exposure at even low levels may threaten children. A few years ago, scientists at the Environmental Protection Agency concluded that it should be banned altogether.

Continue reading the main story

Yet chlorpyrifos is still widely used in agriculture and routinely sprayed on crops like apples, oranges, strawberries and broccoli. Whether it remains available may become an early test of the Trump administration’s determination to pare back environmental regulations frowned on by the industry and to retreat from food-safety laws, possibly provoking another clash with the courts.

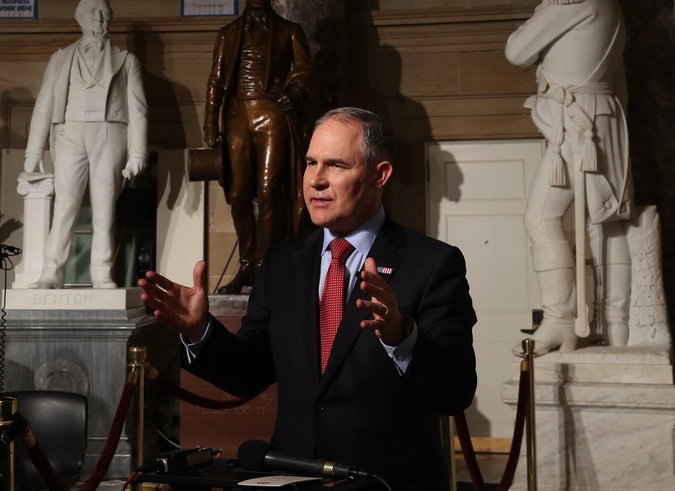

In March, the new chief of the E.P.A., Scott Pruitt, denied a 10-year-old petition brought by environmental groups seeking a complete ban on chlorpyrifos. In a statement accompanying his decision, Mr. Pruitt said there “continue to be considerable areas of uncertainty” about the neurodevelopmental effects of early life exposure to the pesticide.

Even though a court last year denied the agency’s request for more time to review the scientific evidence, Mr. Pruitt said the agency would postpone a final determination on the pesticide until 2022. The agency was “returning to using sound science in decision-making — rather than predetermined results,” he added.

Agency officials have declined repeated requests for information detailing the scientific rationale for Mr. Pruitt’s decision.

Lawyers representing Dow and other pesticide manufacturers have also been pressing federal agencies to ignore E.P.A. studies that have found chlorpyrifos and other pesticides are harmful to endangered plants and animals.

A statement issued by Dow Chemical, which manufactures the pesticide, said: “No pest control product has been more thoroughly evaluated, with more than 4,000 studies and reports examining chlorpyrifos in terms of health, safety and environment.”

A Baffling Order

Mr. Pruitt’s decision has confounded environmentalists and research scientists convinced that the pesticide is harmful.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Farm workers and their families are routinely exposed to chlorpyrifos, which leaches into ground water and persists in residues on fruits and vegetables, even after washing and peeling, they say.

Mr. Pruitt’s order contradicted the E.P.A.’s own exhaustive scientific analyses, which had been reviewed by industry experts and modified in response to their concerns.

In 2015, an agency report concluded that infants and children in some parts of the country were being exposed to unsafe amounts of the chemical in drinking water, and to a dangerous byproduct. Agency researchers could not determine any level of exposure that was safe.

An updated human health risk assessment compiled by the E.P.A. in November found that health problems were occurring at lower levels of exposure than had previously been believed harmful.

Infants, children, young girls and women are exposed to dangerous levels of chlorpyrifos through diet alone, the agency said. Children are exposed to levels up to 140 times the safety limit.

“The science was very complicated, and it took the E.P.A. a long time to figure out how to deal with what the Columbia study was saying,” said Jim Jones, who ran the chemical safety unit at the agency for five years, leaving after President Trump took office.

The evidence that the pesticide causes neurodevelopmental damage to children “is not a slam dunk, the way it is for some of the most well-understood chemicals,” Mr. Jones conceded. Still, he added, “very few chemicals fall into that category.”

But the law governing the regulation of pesticides used on foods doesn’t require conclusive evidence for regulators to prohibit potentially dangerous chemicals. It errs on the side of caution.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

The Food Quality Protection Act set a new safety standard for pesticides and fungicides when it was passed in 1996, requiring the E.P.A. to determine that a chemical can be used with “a reasonable certainty of no harm.”

The act also required the agency to take the unique vulnerabilities of young children into account and to use a wide margin of safety when setting tolerance levels.

Children may be exposed to multiple pesticides that have the same toxic mechanism of action at the same time, the law noted. They’re also exposed through routes other than food, like drinking water.

Environmental groups returned last month to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, asking that the E.P.A. be ordered to ban the pesticide. The court has already admonished the agency for what it called “egregious” delays in responding to a petition filed by the groups in 2007.

Newsletter Sign Up

Continue reading the main story

Please verify you're not a robot by clicking the box.

Invalid email address. Please re-enter.

You must select a newsletter to subscribe to.

Sign Up You agree to receive occasional updates and special offers for The New York Times's products and services.

Thank you for subscribing.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

View all New York Times newsletters.

- See Sample

- Manage Email Preferences

- Not you?

- Privacy Policy

- Opt out or contact us anytime

The E.P.A. responded on April 28, saying it had met its deadline when Mr. Pruitt denied the petition.

Erik D. Olson, director of the health program at Natural Resources Defense Council, one of the groups petitioning the E.P.A. to ban chlorpyrifos, disagreed.

“The E.P.A. has twice made a formal determination that this chemical is not safe,” Mr. Olson said. “The agency cannot just decide not to act on that. They have not put out a new finding of safety, which is what they would have to do to allow it to continue to be used.”

Devastating Effects

Chlorpyrifos belongs to a class of pesticides called organophosphates, a diverse group of compounds that includes nerve agents like sarin gas.

It acts by blocking an enzyme called cholinesterase, which causes a toxic buildup of acetylcholine, an important neurotransmitter that carries signals from nerve cells to their targets.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Acute poisoning with the pesticide can cause nausea, dizziness, convulsions and even death in humans, as well as animals.

But the scientific question has been whether humans, and especially small children, are affected by chronic low-level exposures that don’t cause any obvious immediate effects — and if so, at what threshold these exposures cause harm.

Scientists have been studying the impact of chlorpyrifos on brain development in young rats under controlled laboratory conditions for decades. These studies have shown that the chemical has devastating effects on the brain.

“Even at exquisitely low doses, this compound would stop cells from dividing and push them instead into programmed cell death,” said Theodore Slotkin, a scientist at Duke University Medical Center, who has published dozens of studies on rats exposed to chlorpyrifos shortly after birth.

In the animal studies, Dr. Slotkin was able to demonstrate a clear cause-and effect relationship. It didn’t matter when the young rats were exposed; their developing brains were vulnerable to its effects throughout gestation and early childhood, and exposure led to structural abnormalities, behavioral problems, impaired cognitive performance and depressive-like symptoms.

And there was no safe window for exposure. “There doesn’t appear to be any period of brain development that is safe from its effects,” Dr. Slotkin said.

Manufacturers say there is no proof low-level exposures to chlorpyrifos causes similar effects in humans. Carol Burns, a consultant to Dow Chemical, said the Columbia study pointed to an association between exposure just before birth and poor outcomes, but did not prove a cause-and-effect relationship.

Studies of children exposed to other organophosphate pesticides, however, have also found lower IQ scores and attention problems after prenatal exposure, as well as abnormal reflexes in infants and poor lung function in early childhood.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

“When you weigh the evidence across the different studies that have looked at this, it really does pretty strongly point the finger that organophosphate pesticides as a class are of significant concern to child neurodevelopment,” said Stephanie M. Engel, an associate professor of epidemiology at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Engel has published research showing that exposure to organophosphates during pregnancy may impair cognitive development in children.

But Dr. Burns argues that other factors may be responsible for cognitive impairment, and that it is impossible to control for the myriad factors in children’s lives that affect health outcomes. “It’s not a criticism of a study — that’s the reality of observational studies in human beings,” she said. “Poverty, inadequate housing, poor social support, maternal depression, not reading to your children — all these kinds of things also ultimately impact the development of the child, and are interrelated.”

While animal studies can determine causality, it’s difficult to do so in human studies, said Brenda Eskenazi, director of the Center for Environmental Research and Children’s Health at the University of California, Berkeley.

“The human literature will never be as strong as the animal literature, because of the problems inherent in doing research on humans,” she said.

With regard to organophosphates, she added, “the animal literature is very strong, and the human literature is consistent, but not as strong.”

If the E.P.A. will not end use of the pesticide, consumer preferences may.

In California, the nation’s breadbasket, use of chlorpyrifos has been declining, Dr. Eskenazi said. Farmers have responded to rising demand for organic produce and to concerns about organophosphate pesticides.

She is already concerned about what chemicals will replace it. While organophosphates and chlorpyrifos in particular have been scrutinized, newer pesticides have not been studied so closely, she said.

“We know more about chlorpyrifos than any other organophosphate; that doesn’t mean it’s the most toxic;” she said, adding, “There may be others that are worse offenders.”

Correction: May 18, 2017

An article on Tuesday about the pesticide chlorpyrifos described acetylcholine incorrectly. It is an ester of choline and acetic acid, not a protein. The article also misstated part of the name of a court that was asked to ban the pesticide. It is the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, not the Ninth District.

Follow @NYTHealth on Twitter. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.

A version of this article appears in print on May 16, 2017, on Page D1 of the New York edition with the headline: E.P.A. Lags on Pesticide Action. Order Reprints| Today's Paper|Subscribe

Continue reading the main storyRead the Original Article