‘2 Bitter Options’ for Syrians Trapped Between Assad and Extremists

BEIRUT, Lebanon — When pro-government forces retook her hometown from Syrian rebels, Nisrine accepted the same surrender deal the government has offered tens of thousands of Syrians: a one-way bus trip to a place she had never been — the northern, rebel-held province of Idlib.

Since Syria’s war began, the population of Idlib has doubled as it has taken in a motley mix of fleeing civilians, defeated rebels, hard-line jihadists and those like Nisrine who have packed up their families to ride the government surrender bus.

But as government forces wrap up a blistering campaign in eastern Ghouta, Idlib is likely to be the next target. And this time, there will be nowhere else to run.

“Maybe this is the last chapter of the revolution,” Nisrine, 36, an Arabic teacher from the onetime tourist resort of Madaya, said in an online interview recently. “Syrians are killing Syrians. Nothing matters anymore. We decided to die standing up. I’m sad for the revolution, how it’s gone, how people called for freedom and now it’s gone.”

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Idlib, a small, conservative province on the Turkish border, is Syria’s largest remaining rebel-held area. One of the earliest regions to revolt against President Bashar al-Assad, it may be the place where the revolution that began more than seven years ago finally ends.

TURKEY

100 miles

Aleppo

Idlib

IDLIB PROVINCE

SYRIA

LEBANON

Madaya

Damascus/Ghouta

By The New York Times

The government has carried out scorched-earth airstrikes there with its ally, Russia, routinely hitting hospitals and clinics, schools and neighborhood markets.

Continue reading the main story

But people are still coming.

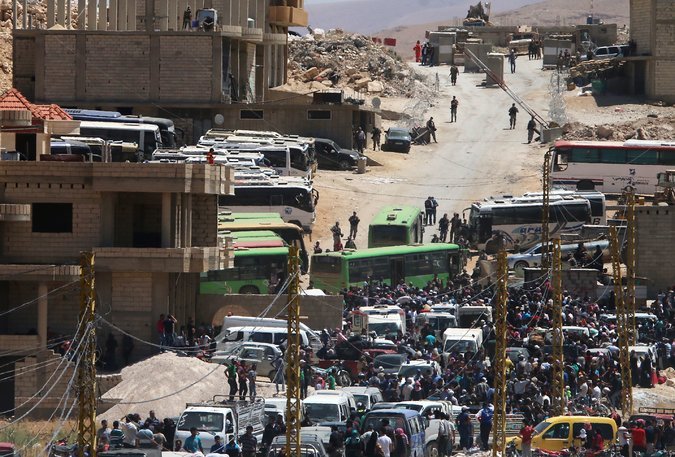

In recent days, more than 10,000 fighters and civilians have been bused to Idlib from surrendering sections of eastern Ghouta. They arrive traumatized, exhausted and disillusioned, often with children suffering from malnutrition after years of siege.

The government has treated the province as a dumping ground for those it does not want in its territory, and paints the province as a nest of jihadists. But the vast majority in Idlib are civilians, including nonviolent activists who could face arrest and torture if they remained in government areas and who often push back against hard-liners in the province they believe have co-opted the revolt.

Marwan Habaq, who survived the barrages in eastern Ghouta in a basement with his wife and infant daughter Yasmina, is taking them to Idlib. It is a tough choice because, as they have no place to live in Idlib, they will have to leave his wife’s parents behind and they will face more shelling. But if they stay, he is sure he will be arrested or forced into military service.

“Two bitter options,” he said. “Leaving to the unknown, or staying within Assad’s hands.”

But the move only delays the inevitable.

“It’s a shame on the world,” said Mehran Ouyoun, a member of the opposition council in exile for the Damascus suburbs, which meets in Turkey. “If you approve the war crime of forced evacuation, at least make sure these people don’t suffer again and again.”

Idlib was once controlled by a patchwork of clashing insurgents, some led by American-backed army defectors calling for a civil state. Others, including an Al Qaeda affiliate, welcomed foreign fighters and espoused a spectrum of Islamist ideologies. But hard-liners have seized the upper hand, playing into the government’s portrayal of the region even as they create tensions with residents who oppose them.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

As they struggle to survive, many residents are caught between government attacks from the sky and the overbearing rule of extremist factions that dominate on the ground.

Nisrine joined the revolution at the outset in 2011, pushing for a secular, civil democracy. Like a dozen other Idlib residents interviewed for this article by phone and email, she asked not to be fully identified for fear of retribution from any side.

She boarded a bus for Idlib last year after surviving a year of siege and bombardment, hoping that her son Abdullah, 10, would not starve to death like some children had in her town, Madaya. At first, she was excited to be reunited with her husband, a former law student and rebel fighter who had gone to Idlib two years earlier.

She did not regret leaving Madaya. After the government takeover there, her brother and brothers-in-law were drafted and sent to the front with minimal training. They died in battle.

But Nisrine was troubled by Idlib City’s ubiquitous jihadist billboards, face veils and cafes segregating women and banning them from smoking water pipes. When she wears her usual head scarf and modest coat, religious enforcers lecture her for not veiling her face.

One ultrareligious neighbor spoke constantly of fighting Shiites, never about building a new country. Eventually Nisrine lost her temper.

“Why did you climb on the revolution’s back?” she recalled asking the woman. “I didn’t join the revolution to see this.”

Her husband, Ahmad, who had been a rebel fighter back in Madaya, also struggled to find a way to keep fighting for a cause he believed in. After briefly joining two of Idlib’s main Islamist factions, he quit to become a paralegal.

Newsletter Sign Up

Continue reading the main story

Please verify you're not a robot by clicking the box.

Invalid email address. Please re-enter.

You must select a newsletter to subscribe to.

Sign Up You agree to receive occasional updates and special offers for The New York Times's products and services.

Thank you for subscribing.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

View all New York Times newsletters.

- See Sample

- Manage Email Preferences

- Not you?

- Privacy Policy

- Opt out or contact us anytime

“They considered me an infidel,” he said of the factions, “and I considered them extremists.”

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

But the episode that shocked Nisrine most was the day her son, after a few months playing with other children in Idlib, announced: “I want to join the jihad.”

Horrified, Nisrine decided to set up educational alternatives and start campaigning quietly against the recruitment of children into hard-line religious schools and rebel factions.

She also helped open a chapter of Dameh, Arabic for hug, an organization that provides psychological support and cultural activities.

Umm Abdo, 36, a philosophy professor from Syria’s largest city, Aleppo, takes a more confrontational approach. She fled to Idlib in 2014 for fear she would be arrested after government forces detained her husband.

“I don’t stay silent,” she said. “I’m not afraid of death. Welcome, death!”

She said she does not leave home without a gun.

She could not find work in Idlib’s university; Philosophy had been banned as “polytheism.” So she became a traditional healer, treating mostly women, and found that their already limited freedoms had contracted further under the hard-liners who control Idlib.

She heard from students brainwashed into calling their parents infidels, teenage girls sold into marriage. One woman arrived unable to speak. It turned out her husband had badly beaten her after she caught him cheating.

With a degree in Islamic law, she started defending underdogs in Islamic court. She helped farmers defeat attempts by the factions to take away their lands. She won a divorce for a woman whose father had sold her to a foreign fighter who raped and beat her.

“When we decided to revolt, it was against oppression,” she said. “But today we’re facing the worst oppression.”

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Life in conservative Idlib poses challenges for everyone from relatively cosmopolitan Damascus, but especially for single women.

Rima, a former political prisoner from Madaya, arrived in Idlib divorced with no local family ties or male relatives to protect her. Few landlords would rent to a single woman and one evicted her when she refused his advances.

“Even taxi drivers ask: ‘Why are you single? Why don’t you have brothers?’” she said.

Recently local authorities in Idlib City announced single women would have to live in special camps.

For Rima, the problem was solved when she got engaged. The catch: Her fiancé wants her to veil her face.

“I will,” she said, “not because I’m convinced, but because I love him.”

Fitting in remains a challenge, but there are few options.

“Idlib wasn’t the best choice,” she said. “It was the only choice.”

Anne Barnard and Hwaida Saad have covered the Syrian war together for six years.

A version of this article appears in print on April 1, 2018, on Page A6 of the New York edition with the headline: Syrians Feel Vise Tighten in a Holdout Rebel Province. Order Reprints| Today's Paper|Subscribe

Continue reading the main story Read the Original Article