Supported by

Book Review | Nonfiction

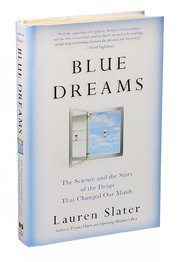

A Reckoning With an Imperfect Science in ‘Blue Dreams’

BLUE DREAMS

The Science and the Story of the Drugs That Changed Our Minds

By Lauren Slater

400 pp. Little, Brown & Company. $28.

In 1988, Lauren Slater put a single cream-and-green pill in her mouth and, with a sip of water, became one of the first patients in the United States to take Prozac. She also emerged as one of its most poetic chroniclers when she detailed her heady, complex love affair with the drug in “Prozac Diary” (1998).

Thirty years since that first dose, neither Slater nor the drug has aged particularly well. Slater, who has spent much of her life wrestling with bipolar and obsessive-compulsive disorders, jumped from an initial prescription of 10 milligrams to 20 to 30 to 60, landing at 80 mg, which is where she left off in “Prozac Diary.” A doctor eventually upped her dose to 100 mg a day — 20 beyond what’s F.D.A. approved. But the drug that had “so magically removed the dead-weight symptoms so that my whole world became a gorgeous glimmer” ceased working once again. Many psychiatrists theorize that each relapse makes the brain more vulnerable to future episodes and leads to a lifetime of antidepressants for people who have had depressive episodes. At the same time, Slater notes, few studies have examined the long-term side effects of these serotonin boosters.

Slater’s current medicine cabinet includes the antidepressant Effexor, the antipsychotic Zyprexa, another antipsychotic, Abilify, the stimulant Vyvanse, the anti-anxiety medication Klonopin, as well as Lisiniprol to combat the high blood pressure caused by Effexor. Add in some of the other psychotropic medications she’s tried — Imipramine, Geodon, Risperdal, lithium — and it starts to read like a pharmacist’s daily fill list.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

But it’s Zyprexa and its side effect of increased appetite that particularly shadows Slater. Her mouth waters at the mention of food. She scoops marshmallow fluff out of a jar and downs several enchiladas at a time heaped with mole sauce. Now at 160 pounds on her 5-foot frame, she is diabetic and in kidney failure, her mouth thick with thirst and her urine thick with sediment. “A single warning from a single doctor when I was in the depths of despair,” she writes, “could not adequately convey the message that by swallowing this new drug I was effectively agreeing to deeply damage the body upon which I rely to survive.” Her attempts to withdraw from medications have proved disastrous: She once bought a gun and another time wrote suicide letters to her children, before retreating back to the blanket of meds again.

Continue reading the main story

The story of Slater’s attempts to get and stay well weaves throughout “Blue Dreams: The Science and the Story of the Drugs That Changed Our Minds” and provides some of the book’s most poignant and lyrical writing. Just as important, her experience makes her a convincing travel guide into the history, creation and future of psychotropics. She is, understandably, not an uncritical cheerleader. But she resists the facile role of hard-charging prosecutor. And no wonder, really, given that the drugs have allowed her to have two children, write nine books, marry (and divorce) and hold dear friendships.

So, when she takes us back to the 1950s and the story of Thorazine, she doesn’t just give us a “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” bag of horrors, but also a glimpse into doctors’ excitement when the drug quelled patients’ delusions and hallucinations and the once-comatose resumed living. A former barber, who had been in a haze for years and for whom all previous treatments failed, returned to shaving (his first customer: the doctor who gave him Thorazine). A juggler asked for billiard balls and began juggling again. And people on one psychiatric ward picked up musical instruments, used drills and saws, held conversations that had been unthinkable shortly before.

In what becomes a through-line in the book, no one fully understood how the drug worked (nor do we know what happened to the juggler or barber once they left the asylum). It was simply enough that it seemed to be working. And yet, in high doses and over the long term, patients often experienced tardive dyskinesia, which includes tongue thrusting, lip smacking, restlessness, involuntary movements of arms and legs, which become twisted like pretzels. When Slater wonders aloud to a psychiatrist why the new class of antipsychotics is really so much better than the old ones, he says: “You have to pick your poisons. Which would you rather be in two years — a circus freak or a diabetic?”

She takes us on similar journeys into lithium and MAO inhibitors, each bringing hope and problems. And then, in the late 1980s there’s the arrival of serotonin reuptake inhibitors, known as SSRIs, and their promise to be different from the antidepressants of the past. The standard explanation is that Prozac, Celexa, Zoloft and other SSRIs boost serotonin levels. But studies have never proved that depressed people suffer from low serotonin (some do, some have normal levels and others have high levels). And SSRIs often fare no better than placebos for mild to moderate depression. Still, doctors tend to talk about depression as if the science is settled, often telling patients: If you’re diabetic you take insulin; if you’re depressed you take a pill. The analogy, of course, doesn’t hold. There is no blood test, no X-ray, no urinalysis that pinpoints depression. It is a field, Slater writes, “still stuttering, with at best a slippery grasp on the science behind its pills and potions, a legion of medical men and women who can help you in one way but hurt you in another.”

Newsletter Sign Up

Continue reading the main story

Please verify you're not a robot by clicking the box.

Invalid email address. Please re-enter.

You must select a newsletter to subscribe to.

Sign Up You agree to receive occasional updates and special offers for The New York Times's products and services.

Thank you for subscribing.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

View all New York Times newsletters.

- See Sample

- Manage Email Preferences

- Not you?

- Privacy Policy

- Opt out or contact us anytime

Hope does arrive in the second half of “Blue Dreams,” when Slater walks us through emerging interventions. Unfortunately, by this point she’s taken us through so much material and still has so far to go — including brain stimulation and memory drugs — that the journey begins to feel too wide-ranging and, occasionally, too thin on details about what we’re passing along the way.

Still, several of the up-and-coming treatments — many of them not new at all — shift our focus from unmediated pill popping. Among them are placebos, which don’t work for all patients and have no effect on those with Alzheimer’s. But, as Slater rightly notes, numerous studies show their amazing potency, which remains too untapped by a psychiatry field still enthralled with drugs.

Like placebos, hallucinogens also aren’t new, of course, but researchers are repurposing them in promising ways. Studies show that psilocybin, the active ingredient in so-called magic mushrooms, curbs smoking addiction, as well as relieves anxiety and depression for people with end-stage cancer. And in clinical trials, psychotherapy combined with MDMA (the chemical more commonly known as ecstasy) offers significant relief for PTSD sufferers. The drug, which creates feelings of empathy and euphoria, allows traumatized victims to recall their terrors in a calm state of mind and establish deep trust with their therapists — ingredients that pave the way for psychological change.

One of the keys for MDMA, psilocybin and some placebo therapies is the connection between patient and provider. And connection is exactly what vanishes during Slater’s own depressive states. Her primary feeling, she writes, is “the loss of love — my people falling away — and the loss of language, my words dwindling so low that my thought seems to move without rhythm or reason.”

It’s no surprise that Slater goes searching for relief among these new treatments. She tracks down a therapist who uses MDMA in her practice. And in the cozy office painted in calming colors, Slater tells the therapist her history and lists her prescriptions. MDMA won’t work for Slater, the therapist tells her; her current medications would block the drug’s effects. Slater knows from past experiences that she can’t risk weening herself from the prescriptions that keep her stable. Her dependency on our terribly imperfect drugs has ruled out her candidacy for more promising ones.

Maggie Jones is a contributing writer at The New York Times Magazine and teaches writing at the University of Pittsburgh.

Follow New York Times Books on Facebook and Twitter, sign up for our newsletter or our literary calendar. And listen to us on the Book Review podcast.

A version of this review appears in print on April 8, 2018, on Page BR15 of the Sunday Book Review with the headline: Matter Over Mind. Today's Paper|Subscribe

Continue reading the main story Read the Original Article