Herbert Kaiser, 94, Health Care Champion in South Africa, Dies

In 1971, an American diplomat named Herbert Kaiser was doing a tour of duty in South Africa when he developed melanoma. It did not escape Mr. Kaiser’s notice that, being white, he received excellent medical attention from a white doctor, while the country’s nonwhite population was chronically underserved by the health system, in part because few medical professionals were people of color.

A decade later, after he had retired from the State Department, Mr. Kaiser and his wife, Joy, thought back on that experience and looked into the disparities.

“We learned that out of a black population of over 20 million in 1984, there were only 350 black doctors, fewer than 20 dentists and less than 120 pharmacists,” Mr. Kaiser recalled in a 2004 commencement address at his alma mater, Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania. “The figures for black infant and child mortality and for maternal mortality were appalling. We saw for ourselves overflowing waiting rooms for sick blacks and hospitals with 300 percent occupancy rates. Figure that one out: It meant two to a bed or on the floor.”

The Kaisers did something about the problem. In 1985 they founded Medical Education for South African Blacks, a nonprofit organization that provided financial and other support to students of color seeking health careers.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Mr. Kaiser died on Friday at his home in Palo Alto, Calif. He was 94. His son Timothy said the cause was heart failure.

Continue reading the main story

By the time the Kaisers’ organization disbanded in 2007 it had helped some 10,000 South Africans of color receive training as doctors, nurses, midwives and more.

The timing of the Kaisers’ initiative proved auspicious in two ways. One was that, when the organization (known by the acronym Mesab) was founded, South Africa was still under apartheid; a more equal health care system and stronger black professional class helped secure the country’s survival when majority rule came in the 1990s. The other was that Mesab began producing health care professionals just as the AIDS crisis was devastating the country.

Herbert Kaiser was born on June 8, 1923, in Brooklyn. His father, Max, was a house painter, and his mother, the former Nettie Slavititski, was a caretaker.

The Depression years were difficult for the family, and Timothy Kaiser said that being on the receiving end of public charity left his father with a sense of obligation that he carried his entire life. After graduating from high school, Herbert worked briefly at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and then, in 1942, joined the Navy, serving on the submarine Dragonet, which was stationed off Japan in August 1945 when the atomic bombs were dropped on that country.

He attended Swarthmore on the G.I. Bill, graduating in 1949, the same year he married Joy Dana Sundgaard, a fellow student. He took a job with the State Department and was posted to Glasgow in 1950. Later in that decade he developed an expertise in Eastern European affairs, and his career included postings to Yugoslavia, Austria, Poland and Romania. He retired in 1983.

Mr. Kaiser was fluent in a number of languages, which enabled him to understand the nuances at play in the politically and socially divided areas where he worked. He needed those skills when he and Joy set up their nonprofit.

Besides the tensions and factions within South Africa, the Kaisers had to deal with the international pressure that was causing many prominent people and companies to withdraw investments from that country. Raising money for their fledgling organization was difficult. But eventually a number of companies, including Johnson & Johnson, Kellogg’s and Pfizer International, signed on, and community leaders in South Africa got behind the effort.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Scholarship money alone, though, wasn’t the answer. The organization found that it also needed to provide other kinds of support for students, both during apartheid and after.

“South African blacks have had to cope with decades of poor primary and secondary education, as well as social neglect,” Saul Levin, Mesab’s chief executive officer, said in 2005. “Students who come into universities from rural areas are shellshocked. I have had students who tell me they’ve never had a bank account or ridden in an elevator.”

Thus, accommodations were made for the program’s students, like allowing them to repeat failed courses or to cut back on their course load if they were having academic trouble. A mentoring program was established.

And Mesab responded to the AIDS crisis with a palliative care program that financed the training of professionals and community caregivers in treating those with the disease.

In addition to his wife and his son Timothy, Mr. Kaiser is survived by another son, Paul; a daughter, Gail; and six grandchildren.

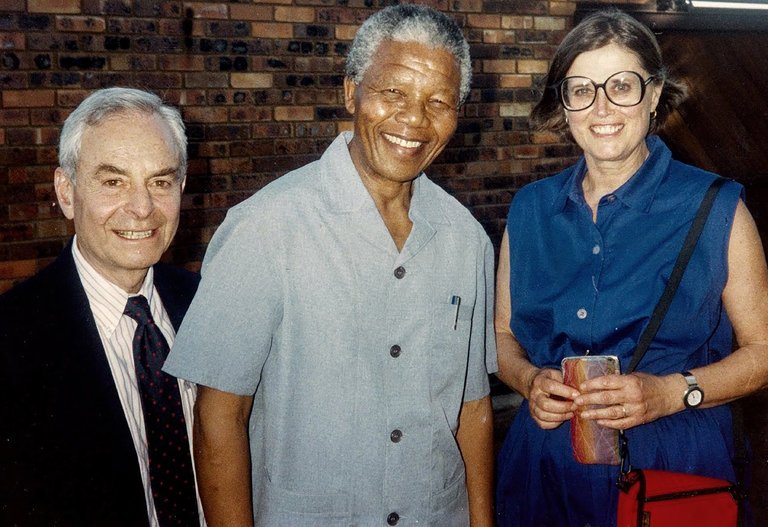

The Kaisers’ efforts, which wound down in 2007, drew praise from some of the leading figures in modern South African history, including President Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu. When, in 2013, the Kaisers published a book, “Against the Odds: Health & Hope in South Africa — The Story of Medical Education for South African Blacks,” the archbishop wrote the foreword.

“If someone had told me in the 1980s that 10,000 blacks would have been trained as health professionals — doctors, dentists, nurses, etc. — in the space of 22 years, I would have recommended that they go and consult their psychiatrist,” Archbishop Tutu wrote.

“And then to add to such an unlikely scenario the prediction that over 27 million U.S. dollars would be raised for this enterprise,” he continued, “would have confirmed for me that someone was in desperate need of psychiatric treatment.”

Continue reading the main story Read the Original Article