The Case of Hong Kong’s Missing Booksellers

Lam Wing-kee knew he was in trouble. In his two decades as owner and manager of Hong Kong’s Causeway Bay Books, Lam had honed a carefully nonchalant routine when caught smuggling books into mainland China: apologize, claim ignorance, offer a cigarette to the officers, crack a joke. For most of his career, the routine was foolproof.

Thin and wiry, with an unruly pouf of side-swept gray hair and a wisp of mustache, Lam was carrying a wide mix of books that day: breathless political thrillers, bodice-rippers and a handful of dry historical tomes. The works had only two things in common: Readers hungered for them, and each had been designated contraband by the Communist Party’s Central Leading Group for Propaganda and Ideology. For decades, Lam’s bookstore had thrived despite the ban — or maybe because of it. Operating just 20 miles from the mainland city of Shenzhen, in a tiny storefront sandwiched between a pharmacy and an upscale lingerie store, Causeway was a destination for Chinese tourists, seasoned local politicians and even, surreptitiously, Communist Party members themselves, anyone hoping for a peek inside the purges, intraparty feuding and silent coups that are scrubbed from official histories. Lam was an expert on what separated the good banned books from the bad, the merely scandalous from the outright sensational. He found books that toed the line between rumor and reality.

Other retailers avoided the mainland market, but through years of trial and error, Lam had perfected a series of tricks to help his books avoid detection. He shipped only to busy ports, where packages were less likely to be checked. He slipped on false dust covers. Lam was stopped only once, in 2012. By the end of that six-hour interrogation, he was chatting with the officers like old friends and sent home with a warning.

On Oct. 24, 2015, his routine veered off script. He had just entered the customs inspection area between Hong Kong and the mainland when he was ushered into a corner of the border checkpoint. The gate in front of him opened, and a phalanx of 30 officers rushed in, surrounding him; they refused to answer his panicked questions. A van pulled up, and they pushed him inside. Lam soon found himself in a police station, staring at an officer. “Boss Lam,” the officer cooed with a grin. Lam asked what was happening. “Don’t worry,” Lam recalls the officer saying. “If the case were serious, we would’ve beaten you on the way here.”

Continue reading the main story

Across the table, Lam recognized one of the officers from his run-in at the same border crossing three years earlier. His name was Li. Beside him sat an older man who identified himself as a member of the national police and who handled the questioning. Why were you bringing books across the border? he asked. “I’m a bookseller,” Lam responded. “There’s no treason in having books while crossing the border.” Li answered with an icy glare.

Partway through the questioning, the older officer got up for a break, leaving Lam alone with Li. The two men sat in awkward silence until Lam, reaching for the conviviality of their last encounter, offered a joke. Li exploded. Lam, he said, was trying to disrupt the Chinese system, and as part of a special investigative unit, it was his job to dismantle Hong Kong’s illicit publishing scene once and for all. Lam was stunned into silence.

Over the next eight months, Lam would find himself the unwitting central character in a saga that would hardly feel out of place in one of his thrillers. His ordeal marked the beginning of a Chinese effort to reach beyond the mainland to silence the country’s critics or their enablers no matter where they were or what form that criticism took. Following his arrest, China has seized a Hong Kong billionaire from the city’s Four Seasons Hotel, spiriting him away in a wheelchair with his head covered by a blanket; blocked a local democracy activist from entering Thailand for a conference; and repatriated and imprisoned Muslim Chinese students who had been in Egypt.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

The campaign signaled the dawn of a new era in Chinese power, both at home and abroad. At a national Communist Party congress in October 2017, President Xi Jinping made clear the party’s expansive vision of control. “The party exercises overall leadership over all areas of endeavor in every part of the country,” he told delegates. No corner of society was out of reach. Even books — “socialist literature,” in Xi’s words — must extol “our party, our country, our people and our heroes.” A few months later, the government erased presidential term limits, opening the way for Xi to rule indefinitely, and put control of all media, including books, in the hands of the Communist Party’s Central Propaganda Department.

The Chinese government has long sought to shape and control information, but the scope and intensity of this effort was something new — and its origins could be traced to a 61-year-old bookseller and a few stacks of forbidden titles. “I never expected anything like this, just as a poor man never dreams of striking it rich overnight,” Lam said. Throughout his ordeal, he had to remind himself that in China, as in his books, the line between the outlandish and the ordinary is often too thin to register. “Contemporary China,” he said, “is an absurd country.”

Ask a publisher in Hong Kong and he or she will tell you that the phrase “banned books” is something of a misnomer. No one within Hong Kong, a semiautonomous Chinese territory, wanted to squash the publishing industry. That dictate came from Beijing and held limited legal force in Hong Kong. For 60 years the city had protection from direct interference, first as a British colony and then, since 1997, under an agreement with Beijing known as “One Country, Two Systems.”

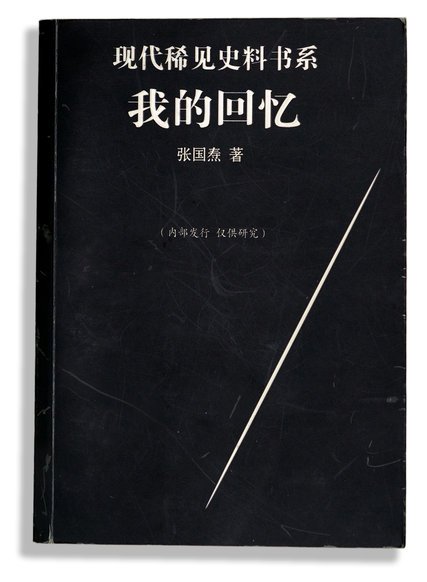

The first important book to be banned was by Chang Kuo-tao, a founder of the Chinese Communist Party and a Red Army general who was both a colleague and competitor of Mao Zedong. Mao ousted him during the power struggles of the 1930s, and Chang settled just across the border in Hong Kong. After years in exile, living in poverty and anonymity, he was discovered by American researchers — still the same handsome, square-jawed man he had been in his youth — and they provided him with a stipend to translate and publish his memoirs.

Chang’s autobiography, released in Hong Kong in the late 1960s, offered a glimpse into the beliefs, motivations and obsessions of Mao at a time when the mainland was almost totally inaccessible to outsiders. Chang portrayed Mao as a ruthless leader, paranoid and inured to the use of violence in pursuit of his goals. Mainland censors denounced the book almost immediately, but in Hong Kong, it was an instant best seller. Aided by an air of forbidden allure and the indication of a huge, untapped market, an industry of similar books began to form.

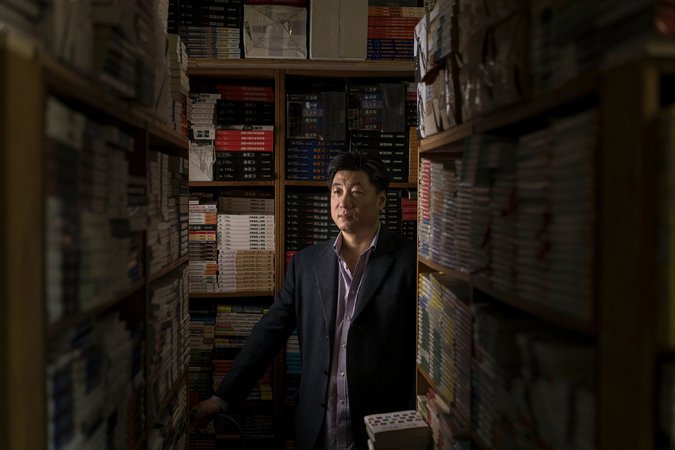

Bao Pu, the founder and publisher of New Century Press, is one of Hong Kong’s most respected independent publishers. When I visited him in November, he found his copy of Chang’s book, “My Memories,” easily, even amid the rows of overflowing shelves that house his personal collection. “Here it is,” he said, carefully turning the yellowed pages. “The very first banned book.”

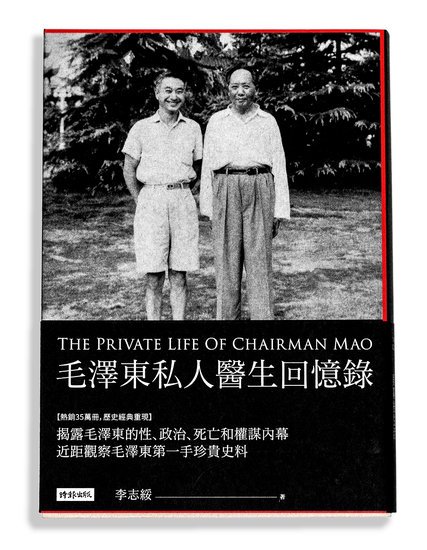

Chang’s memoirs spawned an entire subgenre of Mao biographies, with onetime insiders racing to share every detail of their experience with Communist China’s revered founder. Bao reached for a title written by Mao’s longtime personal physician. “This was the first big banned book after the reforms in the 1980s,” he said, handing me a red-and-black hardcover titled “The Private Life of Chairman Mao,” published in 1994. The book gave an insider’s account of party politics and high-level scheming, but it was the description of Mao’s sexual interests that readers found irresistible. “It was the first time the mainland-owned stores refused a book, and the independent bookstores made a killing,” Bao said. I thumbed through its pages of Chinese text:

At 67, Mao was past his original projection for the age at which sexual activity stops but, curiously, only then did his complaints of impotence cease altogether. It was then that he became an adherent of Daoist sexual practices, which gave him an excuse to pursue sex not only for pleasure but also to extend his life. He was happiest and most satisfied with several young women simultaneously sharing his bed. He encouraged his sexual partners to introduce him to others for shared orgies, supposedly in the interest of his longevity and strength.

In Bao’s library, you could read an alternate history of China, each neatly arranged stack a turning point in modern Chinese politics. The Chinese elite “can’t leak out information in official channels,” says Bruce Lui, a senior lecturer in the Department of Journalism at Hong Kong Baptist University. “So what they can do is use Hong Kong as a platform” to spread gossip anonymously, praise their own camp and belittle opponents. Hong Kong’s publishing houses became an extension of the political battlefield in Beijing.

In 1966, at the start of the decade-long spasm of violence and mass purges known as the Cultural Revolution, universities were closed and millions of supposed bourgeois sympathizers were “sent down” to the countryside for re-education through labor. Dissidents and defectors smuggled out pamphlets, firsthand accounts and other forbidden materials, which circulated in Hong Kong and beyond. During the crackdown that followed the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, Hong Kong’s magazines, newspapers and bookstores were once again a haven for “nonofficial” information. In Bao’s repository, there was an entire shelf devoted to liu si, “6-4,” a reference in Mandarin to the date of the Tiananmen crackdown. For Bao, that shelf alone proved the worth of the industry. He was a college student in Beijing in 1989 and witnessed the whitewashing that followed the Tiananmen protests. “I hate it when history is lost or revised away,” he told me. “The erasure of what happened at Tiananmen is something I won’t allow. It’ll happen over my dead body.”

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

One memoir, by a high-ranking Communist official who had been ousted and placed under house arrest for backing the demands of the student demonstrators, revealed in a firsthand account how the leadership grappled with what to do as the protests grew more popular and widespread:

In the end, Deng Xiaoping made the final decision. He said: “Since there is no way to back down without the situation spiraling completely out of control, the decision is to move troops into Beijing and impose martial law.” … On the night of June 3, while sitting in the courtyard with my family, I heard intense gunfire. A tragedy to shock the world had not been averted and was happening after all.

Alongside the scholarly works and memoirs on Bao’s shelves were tawdrier titles, many of them simply compilations of online gossip. For some members of Hong Kong’s literati, these books were a stain on the city’s reputation. Bao had no interest in publishing fictitious tales of sex and corruption, but he saw a larger purpose in their plotlines. “They reach a different audience, and in their rumor-mongering, they share glimpses of truth,” he said, as he traced his finger across the spine of a salacious, anonymously published work. “They tell the Chinese people that their leaders aren’t saints,” he said. “They’re just like you and me — they’re petty, they make mistakes, they don’t act morally.” Xi Jinping himself was a popular target in titles like “Xi Jinping and His Lovers,” which claimed to reveal the president in his most intimate moments:

Outside the door, Lingling shouts, “Big brother Xi, please help me, I’m in the kitchen cooking dumplings.” Xi Jinping hurriedly runs out, enters the kitchen and embraces Ke Lingling. “My father will be back soon. My father is about to be rehabilitated.”

Lingling quickly pushes him away, saying, “Oh, my, the way you embraced me, others would tease us.”

Bao grew somber as he looked over his collection. After Lam’s disappearance, he said, the mainland had cracked down on banned books with its full might. He knew from his Tiananmen experience what that meant. “There is no way to resist,” he said. “Except to die.”

The morning after his interrogation, Lam was blindfolded, handcuffed and put on a train for an unknown destination. His captors didn’t say a word. When the train came to a halt 13 hours later, Lam’s escorts shoved him into a car and drove him to a nearby building, where they removed his hat, blindfold and glasses. He took stock of his situation: He was in an unknown location in an unknown city, being held by officers whose identity and affiliation he could not ascertain. He still hadn’t been charged with a crime. A doctor arrived to perform a cursory health check. Lam was shown to a cell with a bed and a desk, handed a change of clothes and told to go to sleep.

Lying awake, Lam wondered whether anyone in Hong Kong realized he was missing. What would his family think? Who would tell his ex-wife or his girlfriend in Shenzhen? For years, Lam had owned and managed his bookstore independently, but he had recently sold the shop to a publishing house — maybe his predicament had something to do with their titles? The publishing house, called Mighty Current Media, entered the banned-books market in 2012, with impeccable timing. An ambitious Central Politburo member named Bo Xilai, who some China-watchers thought could be the country’s next leader — ahead of the rising star Xi Jinping — had been implicated, along with his wife, in the murder of a British businessman named Neil Heywood in a Chongqing hotel room. In less than two years, Bo was denounced, demoted and expelled from the party. His wife was convicted of murder and Bo of corruption. A potential future president had been deposed with the world watching.

For Hong Kong publishers, Bo’s downfall was a dream: a real-life soap opera playing out at the very pinnacle of Chinese power. As the market for information on Bo reached a frenzied peak, Mighty Current churned out books chronicling every new development in the scandal. In just one year, there were more than 100 books published in Hong Kong about him, with Mighty Current accounting for half. Bookstores reported sales of 300 copies a day. Mighty Current’s co-owner, Gui Minhai, is believed to have earned more than $1 million in 2013 alone. He bought houses, cars and a property in a Thai resort town. Lam’s bookstore was filled with eager new customers, and in 2014 a group from Mighty Current came inquiring about the store in a bid to combine their prolific publishing output with the shop’s reputation and large customer base. As part of the deal, Lam agreed to stay on as manager — just until he could retire.

At sunrise, Lam was questioned by a tall, dour man named Shi. Who were Lam’s customers? What did they buy? How often did they come in? Later that day, he was presented with forms waiving his right to a lawyer and to contact his family. Still unaware of the severity of his situation, Lam signed them, hoping his cooperation might shorten his detention. The interrogations by Shi and another official continued. As days turned into weeks, Lam began to mark time by secretly pulling a thread off his orange jacket and tying one knot in the string each day. He pretended to use the toilet in his cell in order to climb atop the seat and peer out the window at a few distant hilltops and a handful of nearby buildings, but he saw nothing that would answer the question of where he was being held. In January 2016, more than two months after he began counting the length of his detention, Lam was informed of the charge against him: “illegal sales of books.”

Newsletter Sign Up

Continue reading the main story

Please verify you're not a robot by clicking the box.

Invalid email address. Please re-enter.

You must select a newsletter to subscribe to.

Sign Up You agree to receive occasional updates and special offers for The New York Times's products and services.

Thank you for subscribing.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

View all New York Times newsletters.

- See Sample

- Manage Email Preferences

- Not you?

- Privacy Policy

- Opt out or contact us anytime

Eventually, the questions shifted to Mighty Current’s anonymous authors. Sitting across from Lam, his interrogators produced a stack of banned books, all published by Mighty Current and shipped to China by Lam. One was the company’s risqué “Xi Jinping and His Lovers”; another, published in 2013, outlined the party’s so-called Seven Taboos, a list of forbidden topics and ideas like “press freedom” and “civil society”; a third book remarkably predicted the ouster of a once-powerful general named Xu Caihou.

Who wrote these books? Shi demanded. Lam replied that he was just the bookseller and had never communicated with any of the authors. This was true — most authors requested anonymity from publishers, and it was almost always granted to protect any well-placed sources. Lam had no idea who the authors were.

Lam’s interrogations would end as abruptly as they began, and he would be left alone in the same solitary cell. “From day to night, no one would talk to me,” he said. “You have a complete disconnection from the outside world. You don’t know what will happen. They can do anything to you.” He grew increasingly desperate. “The wait destroys you.”

In January 2016, unknown to Lam, news of his disappearance spread. Other members of Mighty Current’s staff and its owners had also mysteriously vanished. But sitting in his cell, Lam thought he was alone. It was only after several weeks of solitude that he was allowed even a book to pass the time: “Dream of the Red Chamber,” a classic 18th-century novel. Lam’s captors wanted him to read something wholesome.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

That March, more than four months into his detention, Lam met with his interrogator to sign a guilty plea as a precondition for a possible bail arrangement. A few hours later, to his shock, he was put on a train back to Shenzhen, just north of Hong Kong, where he was taken to the Kylin Villa, a sprawling, sumptuous hotel complex usually reserved for foreign dignitaries and high-level delegations from Beijing. The next night, Lam entered an elegant dining room and saw three familiar faces seated at a large circular table — fellow staff members from Mighty Current. Places were set, and the men were served a dinner.

The group chose their words carefully. With a guard and three security cameras monitoring every whisper, some topics were tacitly off-limits, like the fate of the one person missing from the table: the co-owner Gui Minhai. As the meal progressed, they established that they had all been held in the city of Ningbo, on China’s southeastern coast; three, including Lam, on different levels of the same building, and one, the company’s other co-owner, Lee Bo, in a secluded villa outside the city. “If we cooperate,” Lam remembered Lee telling the other men, “we’ll be released very quickly.”

Lee handed each of his colleagues 100,000 yuan, or roughly $15,300 — an “exit fee” to mark the dissolution of Mighty Current. As the men departed, they did not hug or shake hands. “There was no need to hug,” Lam told me. “We already knew how lucky we were to make it to that point.”

Lam was transferred to a new city for the next phase of his detention. There, he was told he would be permitted to return to Hong Kong, but only on the condition that, upon arrival, he report immediately to a police station and tell them his disappearance was all a misunderstanding. He would then go to the home of Lee Bo and pick up a computer containing information on the publisher’s clients and authors, which he would deliver to China. Only then would Lam be allowed to return to work in his bookstore — but as a mole, the “eyes and ears” of the investigation. He would report who bought which books, documenting each client and sale through text and photos. Lam agreed to the proposal immediately. “After being in prison for so long,” he said, “I was used to their way of thinking.”

On a June morning, Lam arrived in Hong Kong and reported to a nearby police station, as directed. Local officers were expecting him. He cleared his case — telling the police that he had never been in danger — and headed to Lee’s home in order to retrieve the computer. There, finally alone, the men spoke freely about their situation. Lam learned that his bookstore had been bought by a man named Chan, who promptly closed it. According to Lam, Lee also described his own capture and how he had been snatched from the parking lot of Mighty Current’s warehouse building. He urged Lam to comply with the investigators’ demands.

That night, alone in his hotel room, Lam violated the conditions of his limited release, using his phone to search for news about his case. His eyes widened as he scrolled through news reports — hundreds of them, in English, Cantonese, Mandarin, French and Spanish. He saw his name and the names of his Mighty Current colleagues appear again and again. When Hong Kong learned of his abduction, the revelation sparked fear and anger. Headlines denounced the “unprecedented” capture and Hong Kong’s “vanishing freedoms.” Lam saw photos of thousands of protesters marching through the streets, holding posters of the missing booksellers and demanding their release; Lam’s shuttered shop had become a site of pilgrimage. He hadn’t been forgotten but instead had become the center of a movement. Lam sat up all night, the glow of his phone illuminating each new twist in a case that he had lived through but never understood until now.

On the morning he was expected back on the mainland, Lam arrived at the train station with the company computer in his backpack. He paused to smoke a cigarette, then another. Other Mighty Current employees had friends, family or wives on the mainland. “Among all of us,” Lam told me, “I carried the smallest burden.” He thought of a short poem by Shu Xiangcheng that he read when he was young: “I have never seen/a knelt reading desk/though I’ve seen/men of knowledge on their knees.”

After he finished his third cigarette, he searched for a pay phone to contact a local politician named Albert Ho, who was once a frequent customer at the bookstore. A few hours later, Lam was standing behind a lectern amid hundreds of reporters, photographers and news cameras at the Hong Kong Legislative Council. He spoke for more than an hour, describing his capture and detention. His sudden public appearance riveted Hong Kong. Other Mighty Current employees had been spotted in the city, but none spoke about their experience, and when they did, they parroted the same talking points: that their stay on the Chinese mainland had been voluntary and they were now helping authorities with an important case. It was Lam who put words to what the city had feared and suspected all along.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

“It can happen to you, too,” Lam said.

At the time of Lam’s abduction, banned books were everywhere in Hong Kong, sold throughout the city at big-box retailers, specialized cafes and corner convenience stores. Within days of his disappearance, they began to vanish, swept off shelves by mainland-owned shops and frightened independent booksellers. Authors were cowed into silence; presses refused to print sensitive material. The latest act of intimidation occurred this January, when the former owner of Mighty Current, Gui Minhai, who had been granted limited release within China, was abducted again, this time while accompanied by Swedish diplomats on a train to Beijing (he holds Swedish citizenship). When the Swedish government pressed China for details on Gui’s whereabouts, the authorities refused to acknowledge that he had been taken. Gui soon appeared in a videotaped confession, apologizing for his supposed crimes and saying the diplomats had tricked him into boarding the train.

China’s aggressiveness continues to rattle Hong Kong. “In the past, at least they tried to comply with one country, two systems,” said James To, a legislator in Hong Kong. “This time they were blatant.” For many local residents, the lesson was clear. “One day they will come and snatch you back,” To said. “There is no protection at all.”

When I met Lam one balmy night on the streets of Hong Kong, he radiated a nervous energy, eyes perpetually darting and a cigarette never far from reach. He had thought about leaving Hong Kong and making a new life in Taiwan or the United States, but he didn’t want to abandon the city where he was born. Still, he knew that the odds of Hong Kong’s remaining autonomous were slim. “I think Hong Kong will return to China,” he told me. “They have the guns, the jails. We have nothing here in Hong Kong. All we can do is protest peacefully and try to make the world pay attention.”

The police protection that Lam was granted following his return had lapsed by then, and he maintained a studied paranoia about his movements and appearance. “I still have to use different routes and be cautious of everything and everyone around me,” he told me in a conspiratorial whisper. His old bookstore was blocks away. He pulled on a pollution mask and hat, obscuring his face, and we navigated the thick crowds. On the subway, he waited until the last second to hop off, and never rode the escalator. “I use the elevator,” he said. “If someone is following me, they have to get in with me.”

We soon reached a small doorway leading to a grimy staircase. On the second floor was Causeway Bay Bookstore, its wooden door hidden behind metal bars. A large yellow sign was filled with the scribbled notes of well-wishers. “Fight for freedom,” one said. “Come back safe, Mr. Lam,” read another. There remained an unanswered question at the heart of Lam’s disappearance: Of all the city’s rebellious publishers, why was Mighty Current targeted? Did the company insult Xi personally? Perhaps fittingly, there are few facts, but boundless speculation. “Our popularity could not be allowed,” Lam told me. “It caught up to us.”

Lam leaned close to peer through the shop window. There were still books inside, scattered on dusty shelves and wooden tables. “I sold over 4,000 banned books in the two years before I was captured,” he said. “This bookstore has always been at the pulse of Hong Kong, and it hasn’t stopped breathing.” He longed for the store’s resurrection, but it wasn’t coming back.

“What you’re doing is writing an obituary,” Bao, the New Century publisher, told me when we met in November. “A post-cremation obituary of these books.” He seemed almost shellshocked by the swiftness of the industry’s downfall. “I didn’t realize it could all disappear so quickly.”

Alex W. Palmer is a writer based in Beijing.

A version of this article appears in print on April 8, 2018, on Page MM43 of the Sunday Magazine with the headline: The Case of The Missing Booksellers. Today's Paper|Subscribe

Continue reading the main story Read the Original Article